Through bold color, vulnerability, and unflinching honesty, Marlon Portales’s paintings unravel inherited expectations of masculinity. His work pushes beyond stoicism and silence, giving shape to a man who feels, who questions, and redefines strength on his terms.

With $4,000 in his pocket, his luggage and a heart bravely set on his dreams, Marlon Portales arrived in the United States stepping into a new life. For many immigrants, this story resonates with familiarity. For Marlon, it marked the start of a journey rooted in love, transformation, and unyielding artistic vision.

He stayed with his family in Miami the first few months and began a new life in a city where, as he puts it, “having a car is a considered a basic necessity.” He was fortunate to find work at a bronze art foundary, leveraging skills he learned in Cuba, working long nights while continuing to paint and develop his craft.

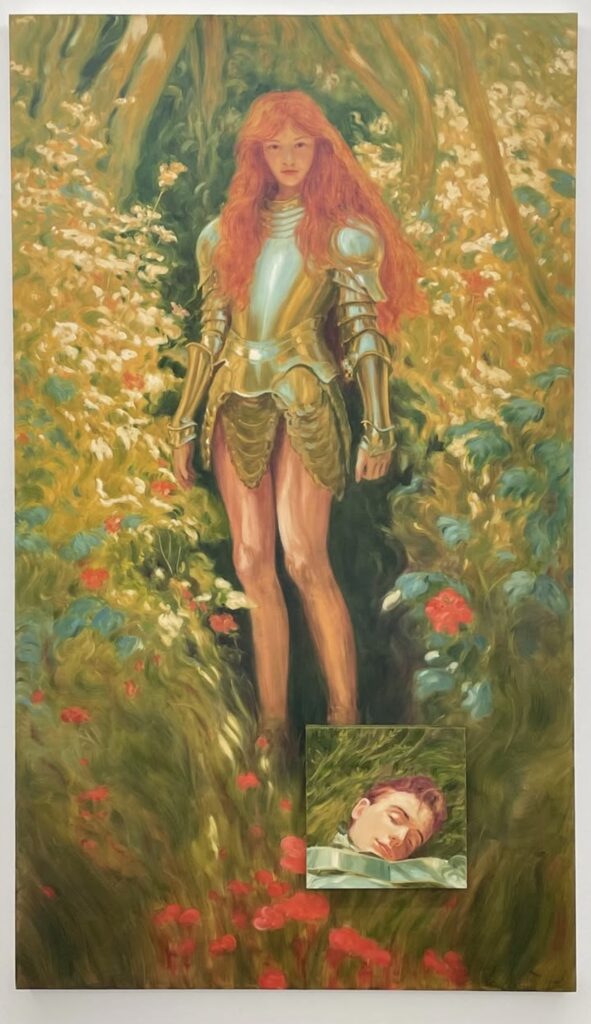

“The Dance” 2025 Oil on Canvas Photo: Courtesy of Spinello Projects

Born in 1991 in Pinar del Río, Cuba, Marlon grew up in the shadows of the “Special Period in Times of Peace,” a euphemism for one of the most economically devastating eras in Cuba’s recent history. With the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cuban government lost its most significant ally and lifeline. Suddenly, food, medicine, and basic necessities became luxuries. But from lack, creativity blossomed. Marlon’s family, despite the harshness of the times, gifted him the most valuable things they could to support his artistic endeavors: the rudimentary tools to explore painting. “I was born during a severe economic and social crisis,” he recalls. “But even in scarcity, there was always a piece of paper and a pencil to draw on.”

Art in Cuba wasn’t just about expression. It was about navigating a highly controlled cultural ecosystem. Marlon had to apply three times to be accepted into Cuba’s top art school, ISA, because his work was deemed too political. “My work had to camouflage itself,” he says. “It had to become more subtle and intelligent in its communication, so it could remain critical without clashing with the government’s cultural agenda.” The Cuban Ministry of Culture sought to channel creativity through a carefully handled pipeline. But instead of silencing Marlon’s voice, this resistance sharpened it. He became savvier about how he presented his ideas, infusing his work with layered meanings, inviting interpretation without overt defiance.

“Red Shoes” Oil on Canvas 2025 Photo: Courtesy of Spinello Projects

The journey to artistic freedom was also a personal test. Before university, Marlon endured Cuba’s mandatory military service, a year of harsh discipline and stifled creativity. “It’s one of those experiences that leaves a mark,” as he describes it, “tragicomedy.” It was supposed to be about preparedness and loyalty, but for him, it highlighted the absurdities of authoritarian control. Cleaning tanks and cutting grass under the guise of training, Marlon found the system both oppressive and ironic. But that same experience fortified his convictions, teaching him resilience and a clearer insight into the power dynamics that art can challenge. During this period in Marlons’ life, he recalls, “Material production was nonexistent, but the mind never stops processing. I remember conceiving a series of conceptual works titled “When a Man Thinks, He Becomes Dangerous,” which unsurprisingly, never saw the light of day.” But that experience, however dark, deepened his resolve. “It brought out the most toxic side of the ‘political animal’ within me, but it also led me to question everything.”

In 2013, an unexpected door opened: Marlon was selected as the youngest artist ever to join the prestigious OMI, International Art Center residency in New York. It was his first trip outside Cuba and a jolt of revelation. “That trip was my window to escape into a whole new universe of inspiration,” he says. “I discovered I only knew a tiny fraction of what we call art. Living on an island means living within many fictions, for better or worse,” a cultural shock in the most exhilarating sense. International artists surrounded him, some decades his senior, exchanging ideas, techniques, and visions. That first breath of global perspective ignited a creative wildfire and inspired a series of over 600 landscapes.

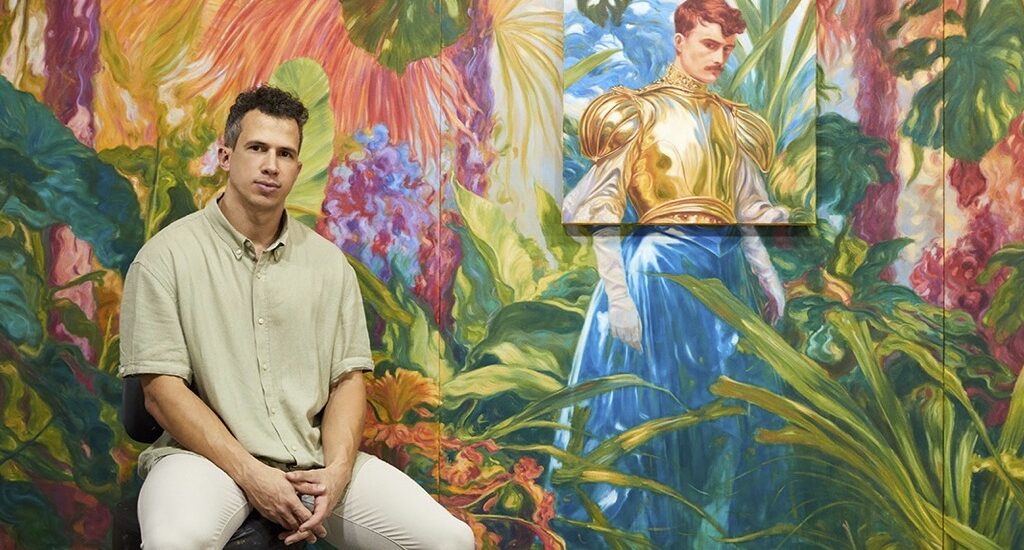

Marlon in Studio Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

After returning to Cuba, he continued to explore new artistic languages while cultivating a relationship that would transform both his life and his work. But what truly anchors Marlon’s journey is love, both romantic and spiritual. His relationship with Gladys, his wife and collaborator, is central to who he is today. A professor of art history at the University of Havana, Gladys brought theoretical depth and curatorial insight to their shared work. They met by chance or perhaps fate when she messaged him “hola” on Facebook just as he was arriving in Miami. That virtual spark withstood distance, bureaucracy, and time. For nearly three years, they lived apart due to immigration barriers, nurturing their bond through longing and creativity. This separation birthed a body of work that explored distance, connection, and the emotional oceans we all navigate. “Those first years of migration, away from my wife and family, were incredibly challenging,” he says. “But despite the distance, we became more connected. That period found its way into my work.” Their long separation inspired his first solo show in the U.S., “Poems of Nature”, a reflection on distance, solitude, migration, and enduring love.

Marlon’s art continues to evolve along with his understanding of essence. In particular, he contemplates masculinity deeply, shaped by growing up in a hyper-masculine society and then being exposed to more inclusive perspectives in the U.S.

“I can’t define masculinity,” he says.” It questions itself. It’s in contradiction with its origins. Since leaving Cuba, I’ve embraced a sensitivity that was always there, one traditionally labeled as ‘feminine’ and seen as derogatory.”

His surreal, pastel-toned, and dreamlike paintings often draw surprises. Some viewers assume a woman painted them. But Marlon embraces that reaction as evidence of the emotional range he chooses to reveal.

“I always analyze my sensitivity, my relationships, and my own story, and that practically encompasses everything.”

Photos: Courtesy of Spinello Projects

His creative process remains an intuitive yet intentional blend of dream and structure.

PM- What changes did you have to make to your art to be accepted into art school in Cuba?

MP-I would say that the most critical moment in my artistic training in Cuba was before entering ISA (Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana). It was a period of rupture and profound transformation, an inevitable process in politically controlled and indoctrinated cultural contexts, at least if you want to fight for your ideals and maintain your inner voice. I graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Pinar del Río, my hometown, and my artistic vision was considered too local and political for the Institute’s standards (or at least that’s what they told me). It took me three attempts to get accepted. I was rejected twice. It was a period of intense experimentation: I worked with video art, performance, installation, and animation… I had to abandon painting almost entirely. In the end, I’m grateful for that experience. It forced me to open my eyes, though not in the way those academics had intended. The reality is that I never stopped painting.

PM- Tell us about your experience with mandatory military service in Cuba and how it affected you.

MP-Mandatory military service is one of those experiences every young Cuban is forced to go through. For over a year, my career and artistic practice came to a complete halt after graduating from the Academy. Creating anything was impossible due to the harsh conditions and strict discipline in the military camps. During that period and in the years that followed, I transitioned from having a highly politicized, reactionary mindset to completely losing faith and hope in a deep political and social change in my country. That shift is inevitably reflected in my work. That same stance became a weakness when trying to enter the ISA. I wasn’t what they expected.

“The Man Who Loved Trees” 2025 Oil on Canvas Photo: Courtesy of Spinello Projects

PM- How was your experience at OMI Art Center and your first trip outside Cuba to the U.S.?

MP-Traveling outside the island for the first time is an experience of deep spiritual and existential dimensions. For Cubans, it’s even more so, given the control and isolation we’ve endured for decades. That first trip and my participation in the residency were eye-opening and transformative for my artistic vision. At the time, I was in my first year at ISA in Havana, and at 23 years old, I became the youngest artist in the residency’s history. That trip was my window to escape into a whole new universe of inspiration and sensibilities. I discovered that the world wasn’t inside a bubble and that I only knew a tiny fraction of what we call art and artistic practices. Living on an island means living within many fictions, for better and for worse.

PM- In your view, what is masculinity today? How has it evolved?

MP-I can’t define what masculinity is today; it’s too abstract a concept to grasp in my hands. But I can speak about my masculinity, one that questions itself, that is in transformation, in learning, in denial, in contradiction with its origins and its present. When I think about it, I always end up analyzing my sensitivity, my relationships, and my own story, and that practically encompasses everything.

Growing up in Cuba and Latin America means growing up in a deeply patriarchal, sexist, homophobic, and racist culture. A culture that historically showcases what we might call the most toxic and oppressive forms of masculinity, where you can either be a victim or a perpetrator. I often ask myself: how can we choose to be different when we’re so young if we see no other models beyond our grandfathers, fathers, leaders, paradigms? I always think of my mother.

Two events were crucial in embracing a more open and flexible masculinity: meeting my wife and migrating out of my country. Listening to and understanding Gladys, her way of seeing the world and of seeing me as the person she chose, has been essential. It’s a long journey.

Since leaving Cuba, my universe has expanded and freed itself from many burdens and prejudices. It has allowed me to be freer and to embrace a sensitivity that has always been there, one that was traditionally labeled as “feminine“, and seen as derogatory in conservative and traditionalist contexts.

“The Duel” Oil on Canvas Photo: Courtesy the Portray Magazine

PM- How did growing up during the “Special Period” in Cuba affect your upbringing?

MP-I was born in the early ’90s, during a period of severe economic and social crisis in Cuba. Looking back now, I think a lot about the effort my parents had to make to raise me, to provide me with health care and education despite the scarcity. If there’s one thing Cubans can be grateful for in times of crisis, it’s that these times have made us more creative in finding ways to survive and move forward. It injected us with resilience and optimism that have been invaluable to this day.

PM- What have you learned about adapting to different cultures, and how has it benefited you?

MP- Adapting to a new culture is essential if you want to engage in dialogue with it, if you want to have a voice and an opinion on any phenomenon, if you want to be part of it. For me, it has become increasingly important to let go of biases and to deconstruct the archetypes and structures that both my local culture and global culture have ingrained in me.

PM- How did you manage being away from your wife for those years, and how did it inspire your art?

MP-Those first years of migration, away from my wife and family, were incredibly challenging, both emotionally and spiritually. They also coincided with the COVID crisis. Despite the isolation and distance, it forced us to be even more connected and present for one another.That period inevitably found its way into my work. Art, for me, is a way of life, a form of resistance, and, as Richter said, the highest form of hope.

Nearly three years after moving to Miami, I presented my first solo show in the city, “Poems of Nature,” entirely dedicated to my visions and mental states shaped by migration, distance, solitude, and love.

“Still Life” 2023

PM- Your paintings combine pastel colors and surrealism, and are sometimes inspired by dreams. How do you decide what makes it onto the canvas?

MP- My paintings stem from my sensitivity and my interaction with the world and human consciousness. What we see as the final artistic result is just a small fraction of our lives that we choose to reveal.

While there’s a great deal of premeditation and symbolic construction in my works, there’s also a lot of intuition and spontaneity. That balance is essential.

“Art, for me, is a way of growing. It’s a vital and spiritual necessity.”

“Portrait of an Artist” Photo: Courtesy of Portray Magazine

Ultimately, Marlon sees art as more than craft. From a boy sketching with scarce supplies in Cuba to an artist painting his truth in a new land, Marlon proves that even in the face of silence, art speaks. His work does not argue sexuality, it dismantles the rigid suppressed expectations imposed on men: Marlon’s message makes clear that expression is autonomous. It is validation of life and evidence of will. It is the voice that endures, rewriting what freedom means.

Marlon and his wife Gladys 2017

Marlon will be having a solo booth at Spinello Projects in the Armory Show, NY Sept 4-7 2025

Comments