Chloe Chiasson brings you to a place where the earth smells like dry grass, cracked, worn leather, and warm nights. Her work softens Americana’s hard edges, peeling back nostalgia to reveal a restless heart. Her creations are shelters of feeling, built from wood, paint, and memory, where past and present blur, but her truth undeniably hums through each work.

Photo: Courtesy of Rose Marie Cromwell and Fountainhead Residency

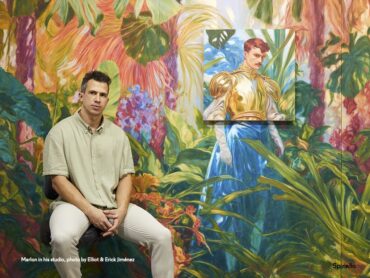

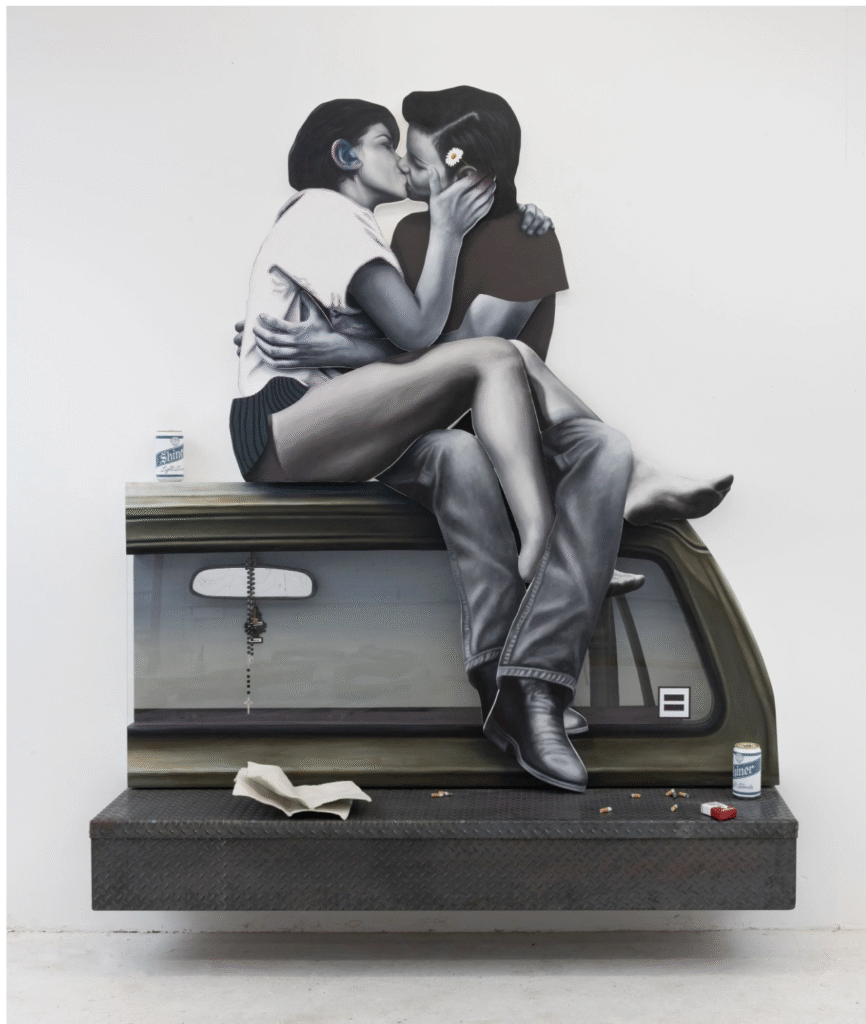

I vividly remember meeting Chloe. I walked down a few worn steps into a studio at the Fountainhead Residency, where I found her working on a wall sculpture of a life-size wooden pickup truck. It was like watching a black and white tv show. Inside sat a figure, not as rugged as a cowboy from old ads, but a more subdued version, carved from longing and courage. The rearview mirror that stuck out whispered, Look back, but keep moving. I wanted to jump in. I remember being impressed with the weight and scale of it, and I thought to myself, “Go big or go home” and that is precisely what Chloe does. Born in 1993 in Port Neches, a quiet Texas town where the main street is lined with a bakery, a candle store, a soda fountain shop, and antique shops. Quintessential small town, USA.

Her art is wrapped in her momories of this place she was raised. And from her memory, a feast of images come to life that make you rethink your own roots. It’s as if Tommy Lee Jones met Larry McMurtry’s depth, served with a drawl and a wink. Chloe followed her intuition and her mother’s nudge toward art school, leading her from a science degree at UT Austin to an MFA at the New York Academy of Art. There, she blossomed and collected honors, including the Belle Artes, Chubb, and Hopper Prize, each a testament to her skill at giving a voice to stories long hushed. Now in Brooklyn, she wields wood, paint, and collage, dismantling old norms with a harmony where rigidity meets smoothness and America needs a new voice.

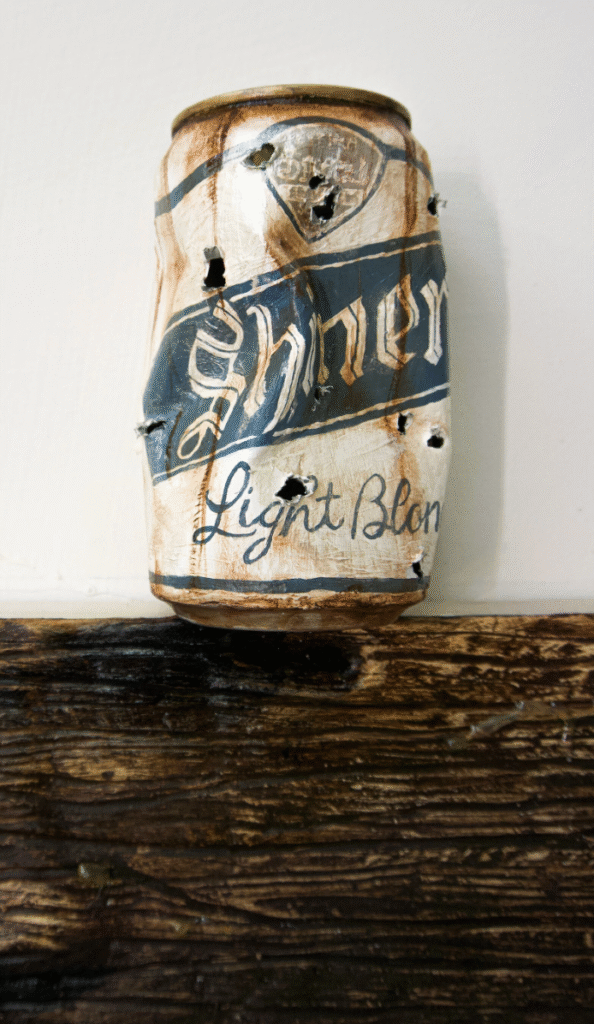

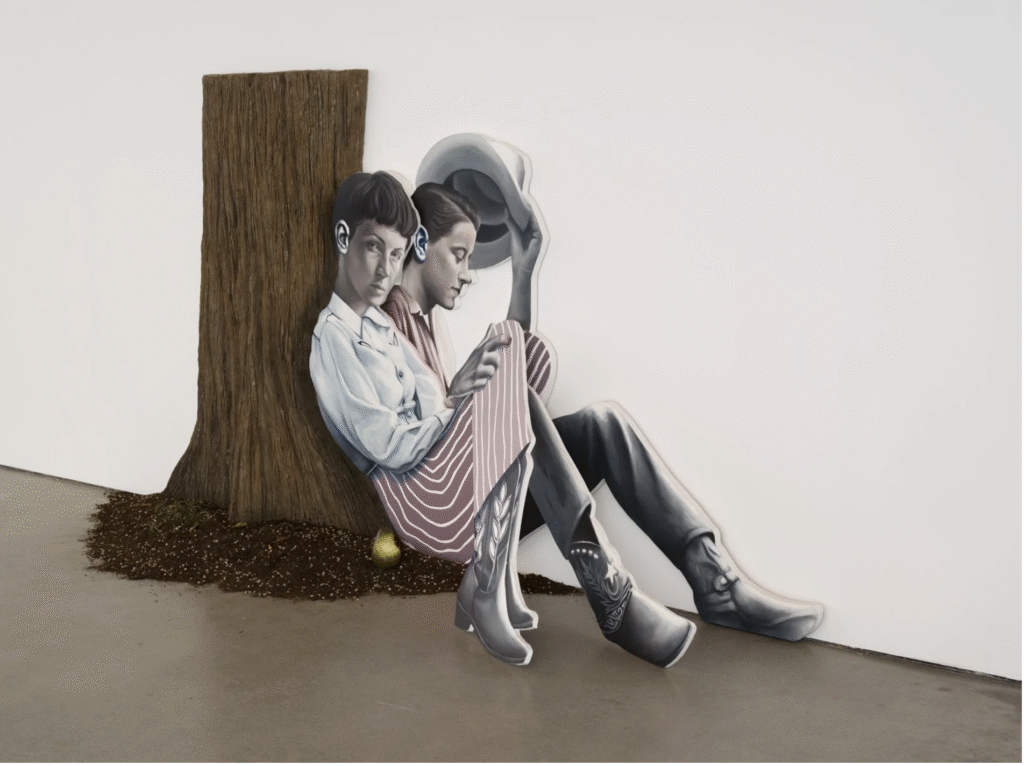

Threading eras together, Chloe crafts histories where individuality isn’t silenced but celebrated. The details she puts into her work are a captivating part of each piece. The engraving, the bite in a pear with teeth marks, the rosary beads hanging from a rearview mirror, the black lanterns hung on a fence, the crushed cigarette butts on a dashboard. Dented, shot up beer cans, the grain in the wood on a tree. There is so much to absorb and identify with. Its all in there, the love and ache, memories of home and escape, offering someone a place to rest in shared memories we all have of longer days and better sleep, and as she continues to grow and expand upon her truths it will all no doubt reflect in Chloe’s beautifully, unique way.

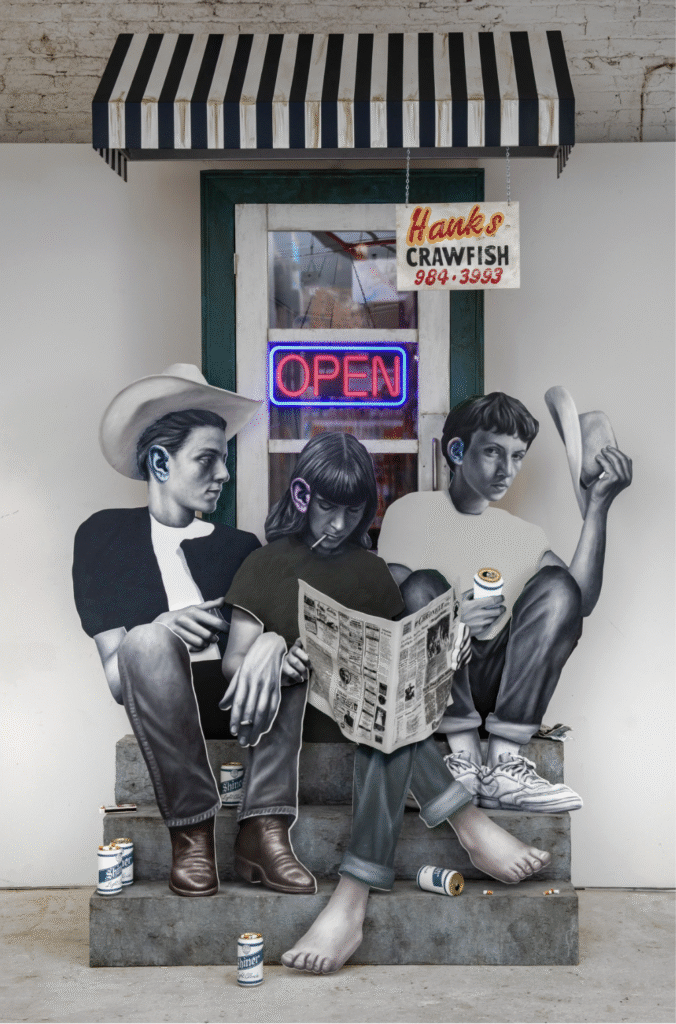

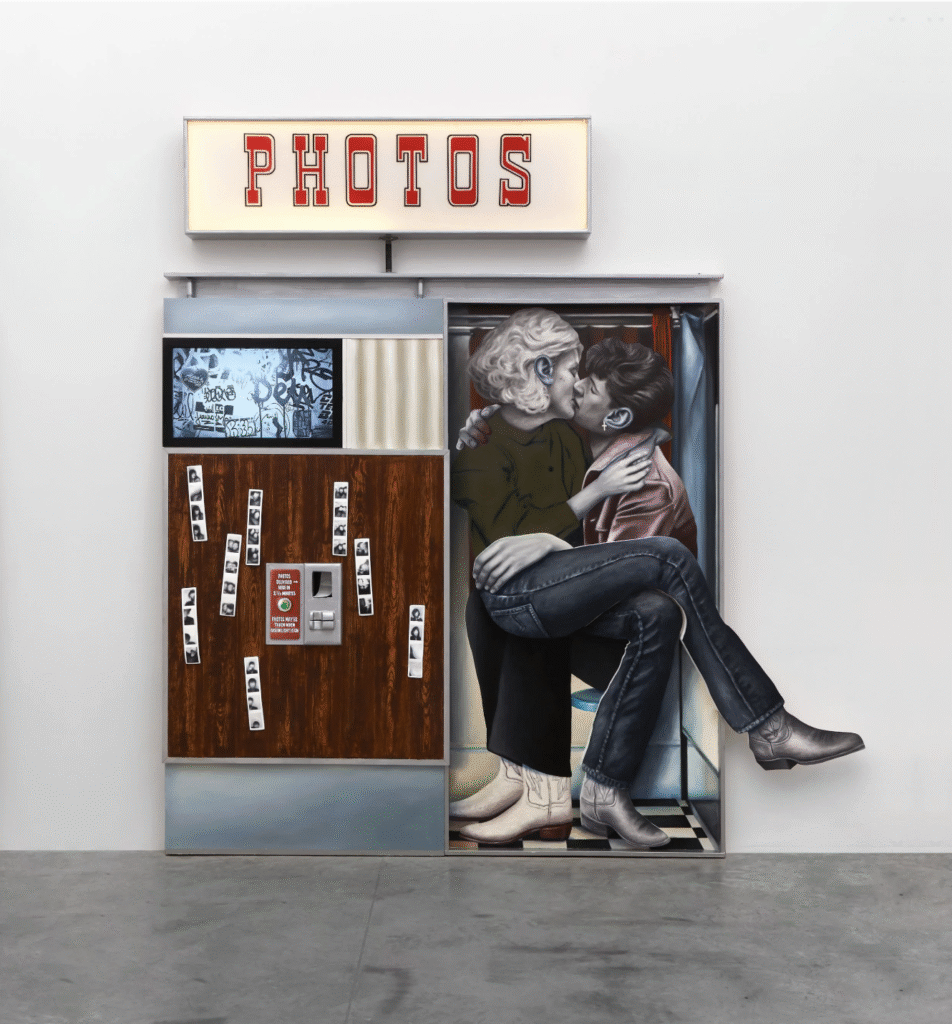

Chloe’s exhibitions crack open the undercurrents of small-town Americana. Her breakthrough solo exhibition, Fast Hearts and Slow Towns, at Albertz Benda in New York in 2022, consisted of nine sprawling installations that fused oil-slicked wood with plexiglass, making rural stoops stages. Critics couldn’t get enough. Artsy hailed it as a “resilient depiction of queer visibility,” Then came Bird on a Wire that same year at UTA Artist Space in LA, a side-by-side stunner, where Chiasson’s full-scale truck sculptures leaned into the gallery like escaped road-trip confessions. Raw, introspective, and buzzing with the idiosyncrasies of Texas life. The real accelerator hit in 2023 with Keep Left at the Fork at Dallas Contemporary, her first institutional solo show, which was anything but subtle: life-size pickups, chain-link fences with bubblegum, and corner stores glowing under neon judgment, all reclaiming small-town iconography.

The Corner Store, 2023 Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

PM: Growing up in Texas has had a profound impact on you. How has your connection to the South shaped your work and your view of the world? What do you love about Texas? What do you hate about Texas?

CC: Anyone’s home has a profound impact on a person. Texas is in my bones, the pace of it, the colors, the smells, the warmth. I wouldn’t say I hate anything about Texas. At one point, and sometimes still, I did and do feel a sort of disdain towards it in some respects. I think it’s safe to say I went through a pretty intense hate/love, which, in hindsight, was in part a necessity to distance myself from it just enough to become who I am and who I always was. Of course, growing up there, in the obvious sense, a lot of the time I felt out of place, and like I had to change myself to fit. So, now, if anything, really, I’ve learned how to hold space for and love the parts of it that shaped me, which were often the worst parts of it. At the end of the day, what I love about it runs deep. I love the familiarity and warmth of my small hometown. I love the sense of home and place in small towns that is so heavy it really becomes a part of you. But there is always this sort of ache, too. A feeling of loving something so much that it doesn’t quite include you, at least not all of you. I think that’s why my work rests in this place or fixation on my home as my primary visual language. There’s a comfort in Texas for me: a warmth, a rhythm. But there’s also this undercurrent of codes, of what’s expected, what’s “normal.” A duality that I’m constantly unpacking in my day-to-day life in my relationships back home, in my relationship to home, and so, naturally, in my work as well. Visually, I love the dusty iconography of it all, of what Texas is, of what small towns are. And as tough as it can be to maneuver sometimes, I do love the intense duality of it all. It’s generous yet tight-lipped, slow yet intense, tough yet tender.

Chloe Chiasson Photo: Courtesy Rosemary McGowen and Fountainhead Residency

PM: You’ve said you are trying to recreate a version of the South you didn’t have to leave behind. What are some of the key elements of that reimagined South that you’re working to bring to life?

CC: Up to this point in my work, I have been reimagining the South and my home. But the more I work, and as the work evolves, the less I feel like I’m inventing something and the more I feel like I’m just telling the truth from a different angle. Less like an invention and more like an uncovering. With my next body of work, and I think moving forward, there will always be some reimagining and invention to it, but I’m more interested right now in honing in on moments and ideas that are universal, with threads of small town Texas and queerness that inevitably show up in the work, rather than it being the primary focus, less about this idea of rewriting the South and more about expanding it from a different perspective. My goal for this next body of work is less focused on reimagination and more about uncovering the truth beneath the surface, allowing it to speak for itself and exist in softer, more subtle ways.

Photo Courtesy of the Artist

PM: You’ve mentioned reshaping Americana. What elements of traditional Americana do you find most fascinating, and how do you incorporate them into your work?

CC: I’ve always been drawn to Americana. Not in a kitschy or ironic way, but because it’s so visually rich. The colors, the dustiness, the architecture of it, the day-to-day objects and places, how it’s all so familiar that it almost becomes invisible when you’re in it. It’s layered, carrying this romantic idea of freedom, identity, nostalgia, pride, and camaraderie, but beneath that, there’s wear, dust, and loneliness. It’s a language I grew up with, naturally inherited through the landscape of my home. I think that, from a queer perspective, there is a natural “reinvention” in using this language, sometimes showing up as a gentle critique or a softening of it. But, I’m trying to work with it in a way that is natural and inherent for an imagery that carries so much cultural weight. Trying to slow it down, use it as is, but in a way that feels intimate and personal by leaning into its dualities and the cracks you can find in it. It’s heavy, but fragile; tough, but soft around the edges. A tension I like and try to hold in the work. For all of its familiarity, there’s still so much room to question it, reinterpret it, and soften it.

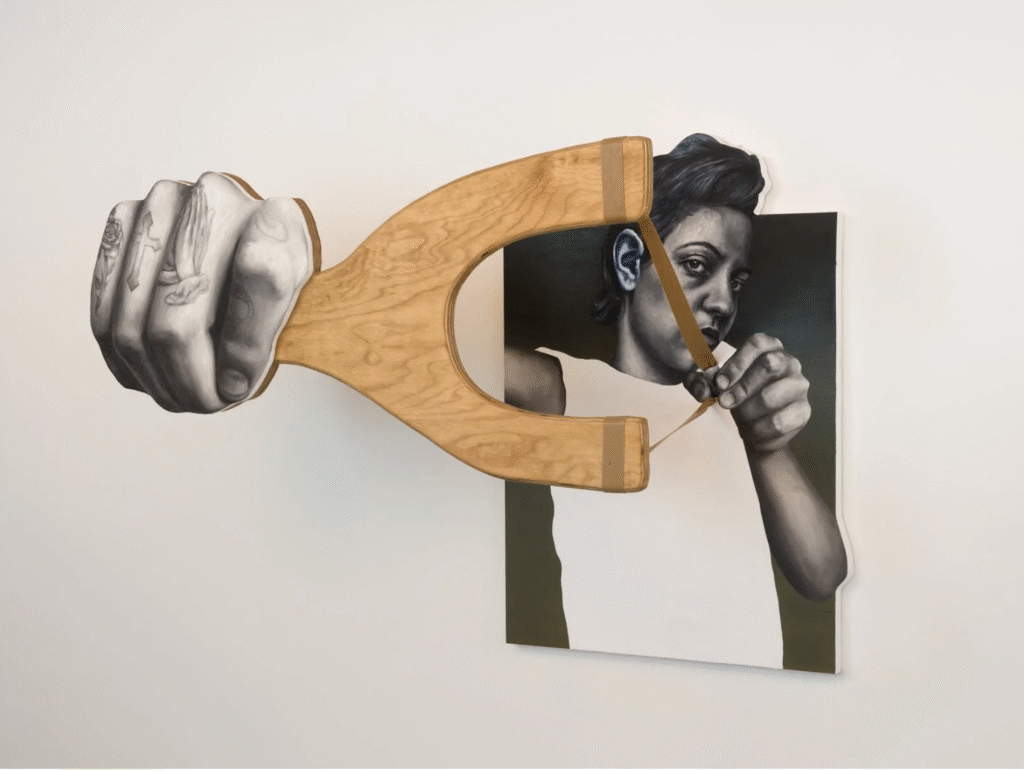

PM: You’ve talked about the concept of “finding personal freedom” through art. Can you speak to how that journey has shaped the spaces you create in your work?

CC: It’s one of those things I didn’t realize I was missing until I found it, and I found it when I started making art. I was suddenly able to build space for myself inside what I already knew, at the same time discovering I was lacking this space all along. It was freeing in every sense; in deciding how a space or an object takes shape, what it holds, and who it holds room for. There’s also this freedom in allowing ambiguity to exist without needing to explain it. Not necessarily freedom as escape, but as permission. Permission to hold complexity, to change shape, to be in process. The spaces I build offer a kind of emotional architecture, somewhere to land, linger, or get lost for a minute. I think that’s what I’ve been looking for in my own life, and the work has given me a way to build it for myself and maybe for someone else, too.

Oh, The Places You’ll Go, 2023 Photo:Courtesy of the artist

Oh, The Places You’ll Go, 2023 Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

PM: Your passion for art and people is so clear. What about the people “in between” resonates most with you, and how do you capture that feeling through your art?

CC: What resonates most is that liminal place where things overlap or resist being pinned down. It’s a place of becoming, of ambiguity, and it feels alive in a way that fixed definitions can’t capture. It’s honest and vulnerable, allowing space for complexity. The people in this sort of “in between” space, which I discussed in my earlier work, are still where the most interesting stories reside for me. The space and moments when identity isn’t fixed, when boundaries blur, and when being fully seen feels both urgent and complicated. That space feels the most genuine to me, because life isn’t tidy. We’re all shifting, adapting, sometimes holding multiple truths at once.The process itself is about negotiation between materials, between memory and imagination, between control and chance. That openness and restlessness is where I’m able to connect with myself, with others, and with the spaces we all inhabit.

Sunday Confessions 2022 Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

PM: What was your experience like coming out at sixteen, and how do you reflect on that moment now in the context of the broader societal shifts happening around queer identities?

CC: My coming out experience was horrifying and liberating at the same time. It was dramatic and messy, but in the end, I had the continued love and acceptance of my family and friends. Reflecting on that moment now, the cultural landscape has changed: there is more openness, a broader range of language, and more space for people to explore their identity and sexuality. But these shifts don’t erase the complexity or difficulty of that experience. This awareness makes me think about how important it is to hold space for those varied experiences, both visible and invisible, the progress made and still being made, and the push and pull of it all. I try to reflect that complexity in the work without simplifying or flattening what it means to live in and through queer identities today.

Saving Grace, 2023 Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

PM: Nostalgia seems to be a powerful tool in your work. How do you use it to create a deeper understanding of both the past and the present in your art?

CC: For me, nostalgia isn’t about romanticizing the past. It’s about holding space for memory’s messiness. I use familiar textures and imagery to create moments that feel both immediate and distant. It’s a way to unpack how identity and history are intertwined, to reveal what has been hidden or overlooked, and to open up new possibilities within familiar places. In creating objects, textures, and scenes that feel worn or lived-in, I’m creating a space where time collapses a little and feels flexible. Where past and present don’t sit apart but overlap and influence each other. This allows me to explore how the past isn’t separate from who we are now, but rather something that actively shapes us, often in ways we don’t immediately see. Nostalgia in this context isn’t just sentimental, it’s active. It’s about recognizing how the past lives inside us, quietly informing how we move, how we relate, and how we imagine the future. In my work, this means creating layers, both visual and emotional, that prompt viewers to slow down and form a connection, to see the history embedded in everyday objects, and to sense the ongoing impact of that history on their identity. It’s this intertwining of time and feeling, this space where history is not fixed but alive, that I find most compelling and try to explore.

Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

PM: You once said, “Within a queer context, there is nothing more public than privacy.” Can you elaborate on that?

CC: What I meant is that queer intimacy, something deeply personal and private, is often the thing that is most publicized and debated by society. Our relationships, our bodies, and moments meant to be private are scrutinized, politicized, and turned into public debate. So, privacy in this sense becomes paradoxical. What should be a private experience is constantly under a public microscope. It’s a reminder of how visibility for queer people can feel invasive or performative, rather than a simple expression of self.

Chloe’s story is one where her fire forges a world that’s both hers and ours. For her family, it’s a tribute to the roots that hold her; for us, it’s a journey into a terrain where memory and courage collide. Her work stands as a bold, quiet act of reclamation, transforming the familiar into a profound introspection on home and the spaces we claim as our own. Chiasson doesn’t just put on a show; she reroutes the narrative, one colossal mirror at a time. These aren’t footnotes in her story. They’re the mile markers, propelling her from MFA honors to international spots in London, Hong Kong, and beyond, where the work doesn’t whisper; it idles loud, inviting us all to keep driving.