Avery Wheless makes you feel something before you even realize what you’re looking at. Her work doesn’t request your engagement—it harbors it effortlessly.

I’ve met Avery several times, and each time has left a more profound impression. There is a quiet sincerity in how she speaks about her love of family, hiking, and the wisdom she has gathered through life’s twists and turns. Our interview unfolded in gentle stages, like her work itself—thoughtful, layered, and full of heart, expressing the grace she carries and the gift of creativity to share it.

Visually, there’s no rush as you stroll into her world where a subtle earnestness forms an instant rapport between you and her subjects, often friends and loved ones who feel both familiar and mythic, suspended in soft yet hushed potency. There’s warmth in their quiet connectivity. It feels like wandering in on something and being allowed to stay. Her work—whether on canvas or through performance—holds space for intimacy, curiosity, and the subtle beauty of simply being.

“Enmesh” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

Avery was born in North Carolina and was raised in Petaluma, California. She grew in an environment attuned to rhythm, composition, and character. Born into a deeply creative home, Avery was surrounded by art in motion. Her mother, a professional dancer and ballet teacher, infused their world with discipline and grace, while her father, a filmmaker and animator, brought in story, ideation, and light. Their influences shaped Avery’s understanding of form, timing, and emotional openness—elements that now reverberate through her paintings and performances.

From a young age, she trained rigorously in ballet and even danced with the Moscow Ballet during their U.S. tours. Dance was her first language, her first stage. But in her adolescence, an injury interrupted that course. What could have been a loss became something unanticipated: an opening. Avery found a new kind of movement that lived through color, shape, and atmosphere; what she found there—remains at the heart of her work today. The colors she uses—lush greens, soft peaches—feel lived-in, seemingly pulled from the landscapes of her past and the people in her life.

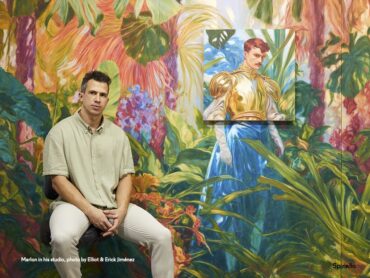

Avery Wheless in Studio Photo: Courtesy of Portray Magazine

That early relationship with painting stayed with her. She went on to study painting at RISD, where she sharpened her eye and deepened her sense of narrative. Eventually, she returned to California, settling in Los Angeles, where her beautiful Downtown studio with high ceilings and great natural light serves as both sanctuary and stage—equipped with a ballet barre for when she feels like a good stretch.

In her performance and video work, Avery extends that invitation further. She creates spaces where the female form is centered not as a spectacle but as a presence—unapologetic, curious, and fluid. Whether painting at residency in Greece, teaching children about painting , she honors the complexity of womanhood with grace and honesty. Her work reminds us that to move is to feel, and to feel is to be seen and a beauty that keeps unfolding long after the moment has passed.

DP- Growing up with a ballet instructor mother and your father who worked in film animation, with these creative influences —can you recall a specific moment from your childhood that sparked your fascination with these themes?

AW- Growing up with a mother who was a ballet instructor and a father working as an animation director, I was surrounded by creativity from an early age. One moment that stands out vividly in my memory is a ballet performance I did as a child, probably at around 8 years old. I remember feeling completely immersed in the role, giving it everything I had. When the performance ended, my mother came backstage with tears in her eyes. That moment was the first time I truly understood the emotional power of art and performance. From then on, I was captivated by that connection—the ability to make someone feel something through art.

“Hannah” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- Can you tell me about the painting of your sister where you felt your talent as a painter truly emerged? When did your family recognize it, too?

AW- One painting of my sister that I did in high school stands out as a turning point. I conducted a photo shoot with her and took a printed-out copy of it for reference. It was the first time I worked with pastels, and I created it while spending time at a local artist’s frame shop—away from home, in a new and inspiring space. She had graciously allowed me to learn from her process, and through her, I began to see color differently. That shift in perception shaped how I approached the piece; the skin tones and shadow shapes became alive. When I finally brought the finished painting home, my parents hadn’t seen any of the work in progress.

Their reaction was pure shock—and honestly, mine was too. It was the first moment I truly felt my voice as a painter, and I think it was the moment my parents, who traditionally always responded to a piece with feedback, had no notes. I felt that they recognized my emerging talent, and I felt truly seen in a new way as a creative.

Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- Can you tell me about the intensity of your experience dancing with the Moscow Ballet during their tour—how did those demanding performances shape your understanding of discipline and expression, especially given your early passion for ballet?

AW- Dancing with the Moscow Ballet was an intense and unforgettable experience. When they toured each year, local dancers would audition for a chance to perform in The Nutcracker. One of the directors, a notoriously strict woman, led the rehearsals. That year marked my first dancing en pointe, and I was cast in the “Dance of the

Snowflakes.” My role was small—I bourréed in the background—but I had to remain on the tips of my toes for the entire piece. During the first rehearsal, I was in excruciating pain. Still too timid to speak up, I pushed

through, holding back tears as we repeated the piece over and over again. When we finally got a break, I removed my pointe shoes and was horrified to see blood already seeping through the fabric. I thought, surely, this would prove that I had tried my hardest, that the pain was too much. I went up to the director, pointed at my feet, and quietly asked if I could do the rest of the rehearsal in flat shoes. She looked at the blood, completely unfazed.

“What would you do during a performance?” she asked.

“I would keep going,” I replied.

“Then why can’t you do that now?” she said.

So I put my shoes back on and finished the rehearsal, a memory that still lingers. I recall the overwhelming desire not to disappoint her and the determination that surged within me. These were the qualities I honed in that demanding, creative, and performative environment. Ballet and the rigorous training it demanded taught me not only how to be strong within my body and endure pain but also what it truly means to persevere. It also taught me how to disassociate—to separate myself from discomfort to meet impossible expectations for the sake of art or life.

“Plein Air Cypress Tree” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- Can you share some memories of the hikes you took with the woman from the frame shop and her friend’s painting—how she came into your life, how those outings unfolded, and what stood out to you about them? And what of those times still lingers in your work today?

AW – Mary Fassbinder came into my life at just the right time. My mother, a longtime customer at Mary’s Frame Shop, realized I needed a mentor and persistently encouraged her to take me on as a student. Mary wasn’t interested in teaching at first—it took about a year before she agreed.

Something clicked when I walked into her shop—we became fast friends. I needed mentorship, and she seemed ready to welcome someone into her creative world. It was a serendipitous match.

Mary took me on outings with her circle of painting friends—most much older than me, some even professors at local art schools. We’d go on hikes, paint plein air, or gather for figure drawing sessions. I learned by watching them, soaking up their techniques, and receiving generous critiques. It was an intimate masterclass filled with encouragement and support. Despite our age difference, they welcomed me as an equal.

Those times left a deep impression. The spirit of curiosity, generosity, and community still lingers in my work. I carry their voices with me, especially Mary’s, whenever I face a blank canvas—telling me, “Just go for it. You know what to do.”

“Too Much To Care” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- You’ve mentioned collaborating with friends and dancers you admire. How do these collaborative experiences shape your creative process compared to working solo?

AW – I love extending my painting practice into more collaborative forms. When I first moved to LA, I knew I wanted to keep my painting space sacred, figure out what I wanted to say, and develop my style before relying on it for income. I was also eager to collaborate with artists in different mediums, which led me to directing music videos that evolved into fashion films and beauty campaigns.

The spirit of collaboration—bringing creative voices together to build a shared vision—has always been at the heart of my studio practice. One of my favorite parts is translating a painting series I’ve spent months developing into a performance piece. These projects unfold organically, and I’ve been lucky to work with inspiring dancers and musicians. Sometimes a musician I’ve worked with on a video will compose a score for a performance, and it becomes this whimsical, evolving game of telephone—an idea passed between voices, layered with movement, sound, and emotion.

It always becomes something more profound than I imagined. These collaborations have taught me to release control—to let a vision grow and shift through the collective process. That openness continues to shape not just my creative work, but how I see the potential of art itself.

“Mutually Exclusive” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- What does this layering of the senses—merging the visual sweep of your paintings, the kinetic energy of Dance, and the narrative pulse of film—mean to you as an artist, and how do you see it transforming how viewers experience the stories you’re telling?

AW- I think, given how I experience the world, working across multiple artistic languages has always felt essential. Painting, Dance, and film—when in conversation with each other—allow me to reach a deeper, more complete expression of what I’m trying to communicate. Each medium brings its energy and perspective, and when they merge, it’s powerful to see them form one cohesive, immersive experience. There are endless ways to create and experience art, and I’ve always been energized by exploring those intersections—constantly pushing the boundaries of my capabilities. I’m especially drawn to stepping into unfamiliar territory, attempting things I haven’t fully mastered. In those exploratory moments, I often discover new ways of saying something I couldn’t have otherwise expressed. And just as that process challenges and excites me as the artist; I believe it invites the viewer to be an active participant in the work—to feel, question, and engage in a more layered and meaningful way.

Avery in Katikia Artist Residency Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP: You did a residency in Greece at Katikía Residency. How was this experience for you creatively?

I try to go into every new body of work with a receptive attitude, but producing on a residency is an added challenge because you are experiencing a new place, working with slightly different materials, and adapting to a new studio setup. Additionally, you are engaging with new people and navigating a new attitude and culture. I am beyond sensitive to all of these things, so I try to lean into my process with understanding and allow mistakes and new outcomes rather than being hard on myself when things turn out differently. It is a gift to process an unknown landscape and culture and make work inspired by it. I tried to integrate this as much as possible and lean into all the newness. In this residency, I have experienced what it means to be removed and present in an unfamiliar environment. While observing people, I interact and engage, but I also have an extra level of outsiderness as a viewer. This body of work celebrates being vulnerable within a new environment—A stage to play and allows an openness to magic and spiritual awareness that is easy to find when things are fresh and new.

“Watching you watch me” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- Tell us about some random jobs you took and how those experiences, whether mundane or unexpected, shaped your resilience, creativity, or even the themes you explore in your art today.

AW – When I first moved to Los Angeles, I wasn’t sure where my career would lead, but I knew I needed a steady job to support myself while making time for painting. I landed a role at Digital Domain, a visual effects company, starting as an assistant to the creative director. My tasks included writing pitch decks and sourcing visuals—work that highlighted my strength in creative storytelling. As the company expanded into AR and VR, I was offered a full-time writing position, which became both a challenge and an opportunity. I dove into screenwriting for emerging tech, attended VR conferences, pitched concepts, and even had the chance to present ideas to Stan Lee and his team.

Working at Digital Domain was invaluable. I was surrounded by artists who had worked on major films and got to visit the motion capture set of Ready Player One to see green screen filmmaking up close. After two years, our team was cut due to the high costs of VR/AR, but by then I had built a base of freelance projects. I started directing music videos, collaborating with musicians and magazines on fashion films, and began a long-term creative relationship with Clarins, a skincare brand I still work with.

During the pandemic, I took on a range of jobs—from working in a vegan cheese factory where we meditated daily, to freelancing as a writer for Artillery Magazine, to sitting as a “gallerina.” Every experience taught me something about adaptability and creative persistence. It was during this time that I saved enough to rent my own studio. As the world stood still, I returned fully to my practice—I began painting like my life depended on it. Not long after, I had a series of studio visits and was offered a solo show at Ochi Gallery, marking a turning point where I committed to my art completely.

“Fitting In” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- Los Angeles is a city of reinvention. How has living there encouraged you to take risks in your art that you might not have considered back home or in Providence?

AW- As I’ve touched on, Los Angeles truly feels like a creative playground. Living here has allowed me to connect with so many artists who are willing but eager to collaborate and bring bold, imaginative visions to life. I’ve been incredibly fortunate that both fellow creatives and brands have trusted me with their ideas—allowing me the freedom to interpret, expand, and run with them. That trust has been deeply affirming and has given me a renewed sense of confidence in my voice, both in film and within my studio practice.

At the same time, LA is fast-paced and, at times, unforgiving. When I first arrived, I had no money, no set place to live, and no job. It was a complete leap of faith. But in many ways, that rawness—the survival challenge—pushed me to grow up quickly and figure out how to make art and sustain a life around it. I’m endlessly grateful for the creative communities here that welcomed, supported, and helped me carve out a space for myself. Living in Los Angeles has taught me that risk is often the path to discovery, and it’s within that tension—between uncertainty and possibility—that some of my most meaningful work has emerged.

“Not All Mine” Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

DP- What have you been reflecting on lately, and how has it impacted your creativity?

AW- Lately, I’ve been reflecting deeply on memories—how they resurface in the present and how time can distort or soften them. I’ve become aware of how, in revisiting these moments, I sometimes step into the role of an unreliable narrator. There’s a tension between seeking clarity in the present and reshaping the past, especially when it involves difficult or painful experiences.

This process has led me to explore how certain traumas might be reframed—not erased but transformed into something that allows healing and beauty. I don’t approach my paintings with a clear, linear narrative, but I see them as a process of layering and re-remembering. They become a space where I can capture a moment and rework a memory—often turning something once hard to hold into something delicate, evocative, and open to interpretation.

I aim for a sense of comfortability in vulnerability and ambiguity that invites viewers to bring their own stories into the image. In that in-between space—between memory and imagination, pain and beauty—I find my creative voice most alive.