Justyna Kisielewicz’s work is like a silk-wrapped grenade. She has a powerful presence, a warm smile, signature flip-up sunglasses, and a laugh that fills the room. Yet, every canvas she unleashes detonates the hidden brutality of empires old and new, turning ration cards into explosions of color that refuse to let you look away.

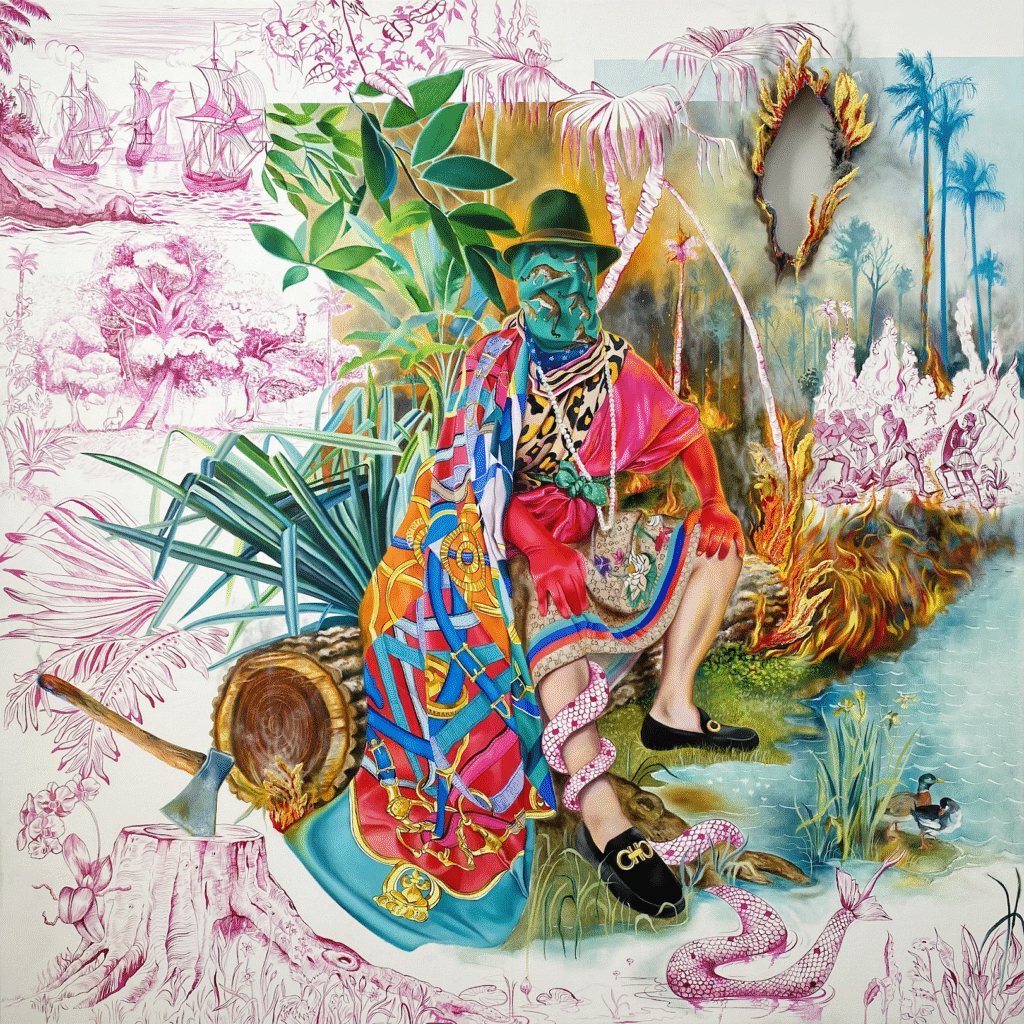

Her paintings, at first glance, may appear to be a celebration of opulence: canvases erupt with oversized figures lounging, draped in rich silk scarves, but their shiny shoes are crushing embroidered heirlooms underfoot. They tell a story wrapped in Baroque drama and big, cryptic pop-culture punchlines, dazzling and loud, right in your face, making you assume you are looking at a piece of trendy pop art.

Until you blink.

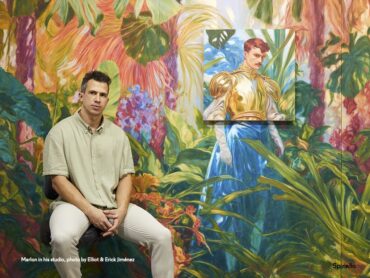

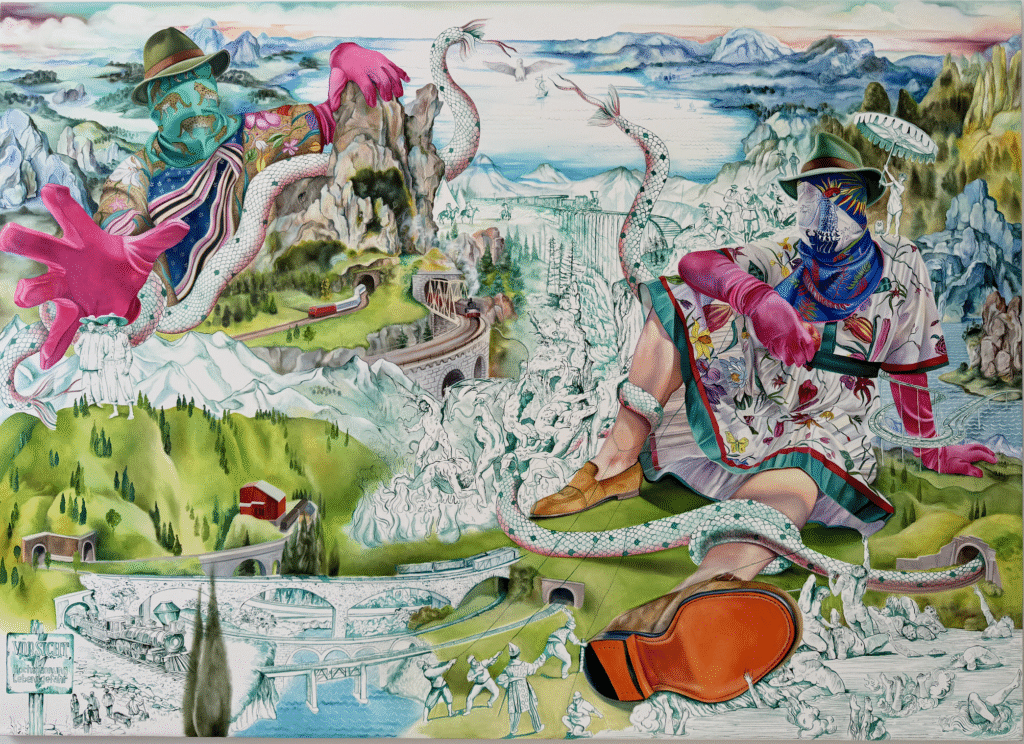

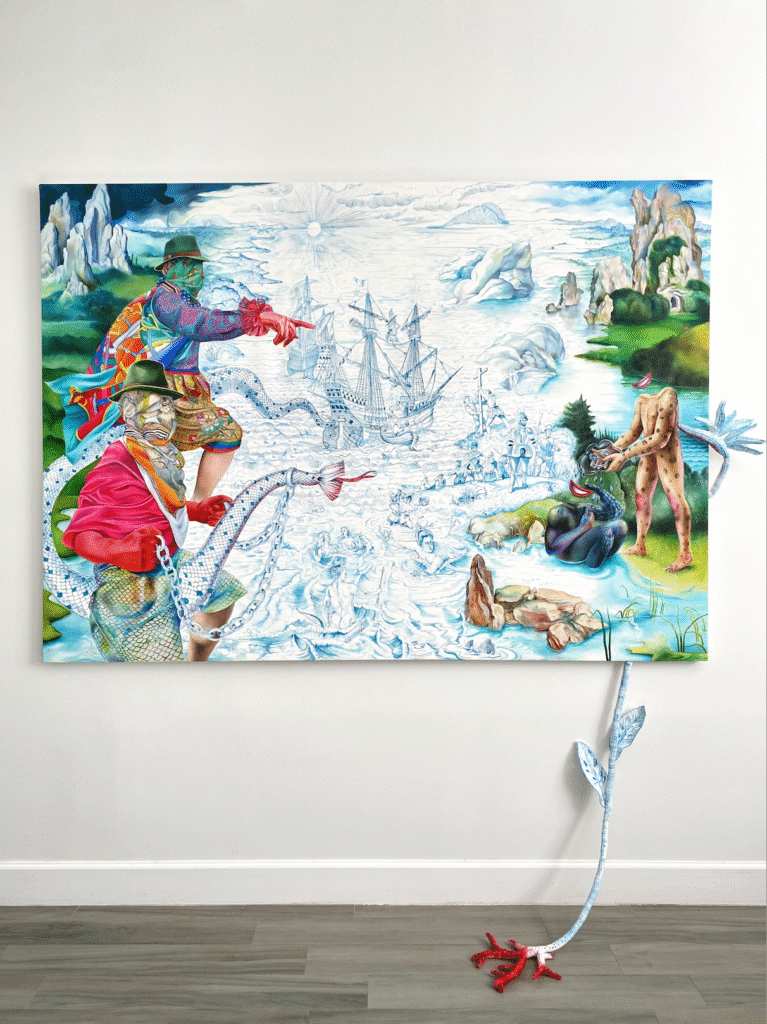

Photo: Courtesy of the Artist “Lebensraum” 2025

Then the feathery stories told behind the aloof, bright images hit you like a ton of bricks when you fix your attention between the lines: they’re packed with the quiet violence of displacement, erasure, and conquest, critiquing colonialism, gentrification, and consumerism. Suddenly, you see the neighborhood ghost underneath the glitz. Although you see animals, and the obvious haute couture references, she is by no means monkeying around.

In the painting above, a small train winds into the mountains—a quiet but unmistakable reference to those taken to concentration camps. Only then do you notice the bodies in the ditch, the tiny figures straining to pull down the person seated comfortably above them, or the servant holding an umbrella over a figure oblivious to the suffering below. Yet amidst the darkness, the sky, the mountains, and the sheer quality of her brushwork pull you in. The drama is undeniable, but so is the beauty. It’s at this moment that you grasp her sharp intellect and let her do the rest of the talking, because she already knows you’ll walk away wondering why the candy tastes like gunpowder.

Coming from Jewish roots in Poland, her family’s story is one of tragedy and rebuilding. Born in Warsaw under the shadow of the Iron Curtain, she came to the US in 2018 via a “Genius Visa.” She has transformed scarcity into spectacle and history’s scars into vibrant expressions of rebellion. For a child in Poland during the 1980s and 90s, the world was a place where the rules changed overnight and the adults around you were always bracing for the next blow. She lived with her mother and brother in a small apartment surrounded by brutalist architecture, martial Law and curfews. In this interview, she tells a story about when she was a young girl around eight years old, the school trip was to a concentration camp. It made an incredible impact on her until today. In her earlier works, she painted pink figures. They were not pink to be pretty. This was the color the bodies turned after they were gassed.

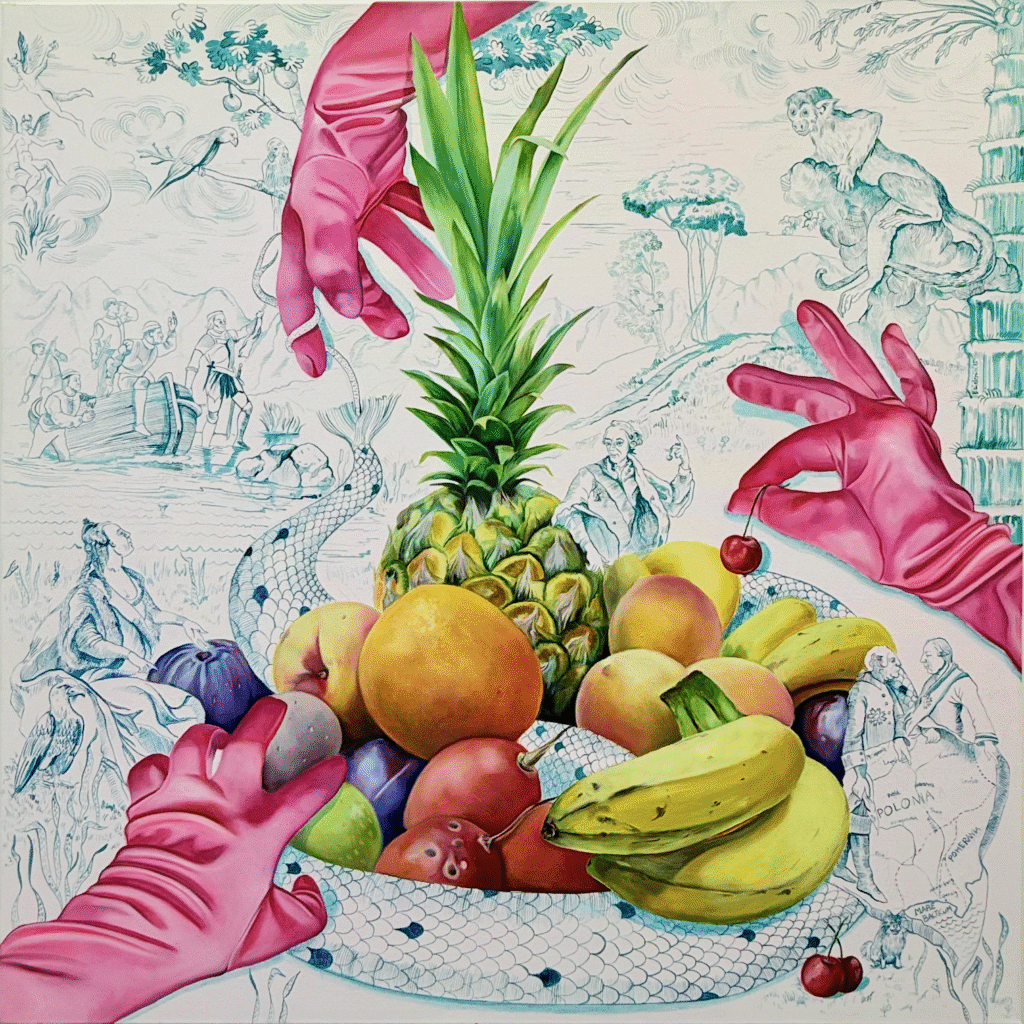

Growing up, she remembers being a happy child, but food came on coupons: maybe you got some chocolate that you split into four pieces to make it last. People would wear the same wool coat for many winters. Maybe the electricity would fail at 6 p.m. You did homework by candlelight. This was her reality. When independence finally came in 1989, the shelves filled overnight with real Coca-Cola, Snickers, and bananas nobody had ever seen in person. Suddenly, hyperinflation took hold and the price tags tripled and kept climbing. Freedom tasted like sugar and panic at the same time.

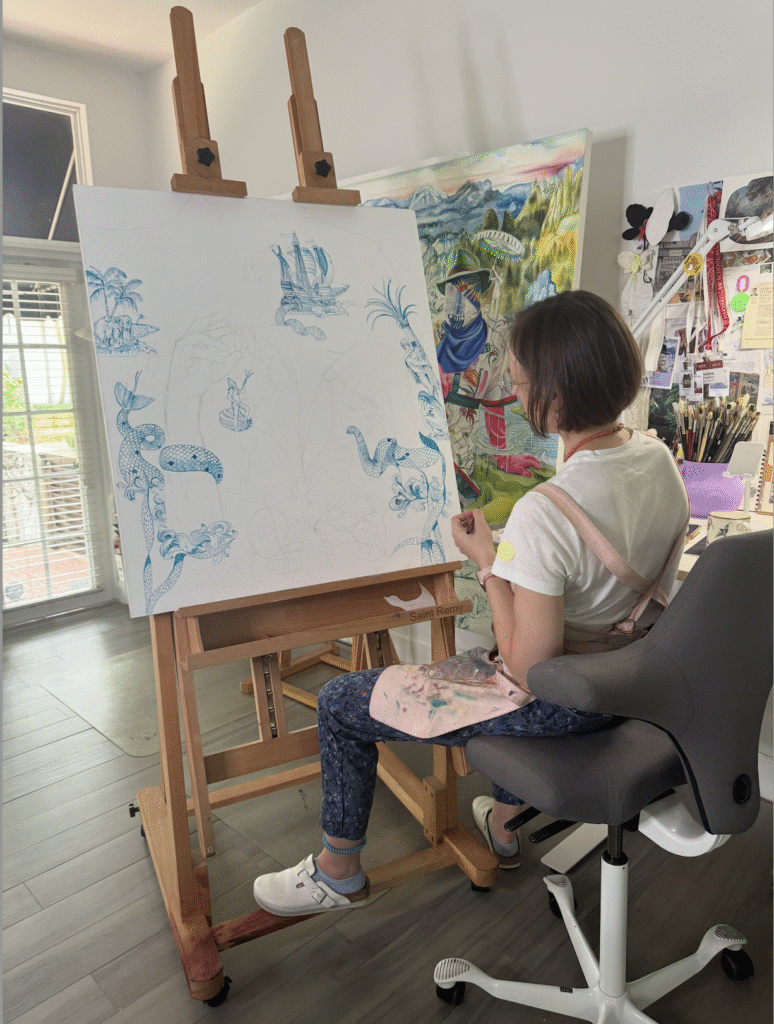

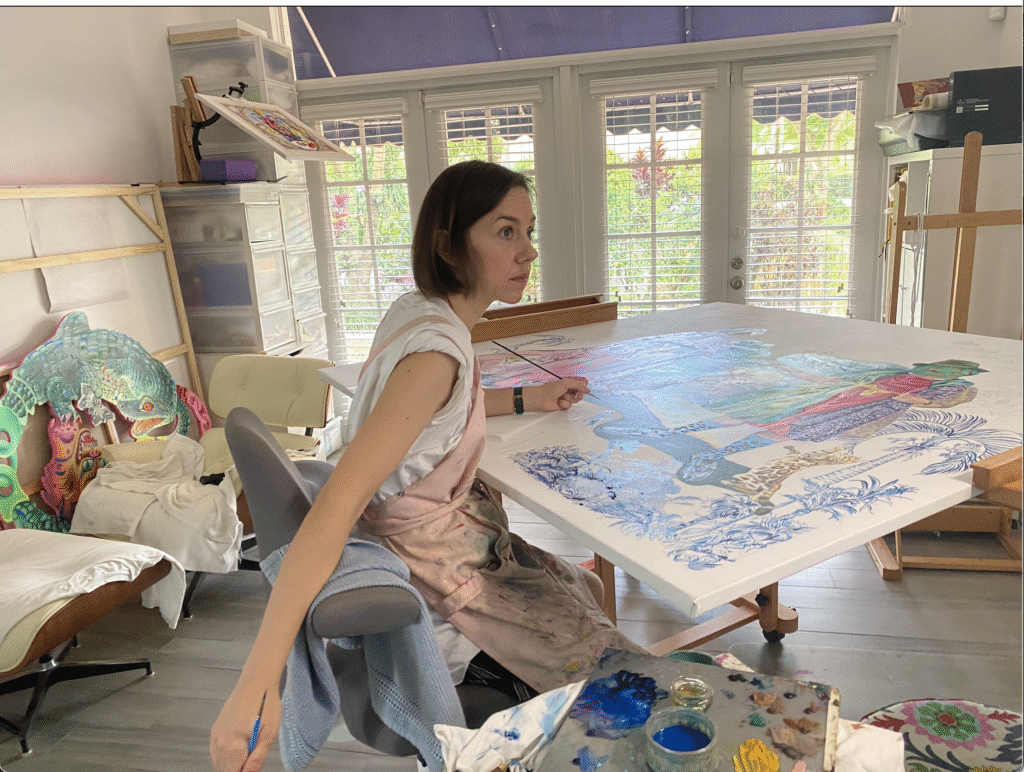

Today, she lives in Miami with her husband and her adorable pomeranian, Charlie Brown, who is almost always tucked at her side or in her arms. She has devoted her life to deepening her practice, living a healthy lifestyle, biking in her free time, and spending Sundays in the lush gardens where much of the foliage in her paintings first takes root. That’s the woman I want you to meet in these pages: grounded enough to remember splitting one chocolate bar four ways, generous enough to still share the last piece, and possessed of the calm, unflinching wherewithal of someone who has lived through real scarcity and come out grateful and radiant on the other side. .

She paints like someone who knows exactly how expensive joy can be. With every candy-coloured stroke she cuts straight through the glamour, then steps back and lets her razor wit leave the room buzzing with the one question nobody wants to ask out loud: What did freedom actually cost, and who is still paying the bill?

“At the Gates of Paradise”

ONE OF MY FAVORITE JUSTYNA STORIES

Justyna earned a Masters degree in Fine Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Poland. at the AIn college in Poland in the Early 2000’s, Justyna was required to take so-called “women’s work” classes, traditional, domestic craft courses that were expected of female students. Instead of accepting the premise, she turned the assignment on its head. Enrolled in embroidery, she stitched bold, unapologetic penises into her textile pieces and handed them in without a word. The work spoke for itself: a quiet, razor-sharp indictment of the sexist expectations built into the curriculum. It was her first rebellious act in a long career of challenging the systems that try to define her.

THE MEDIUM IS THE MESSAGE

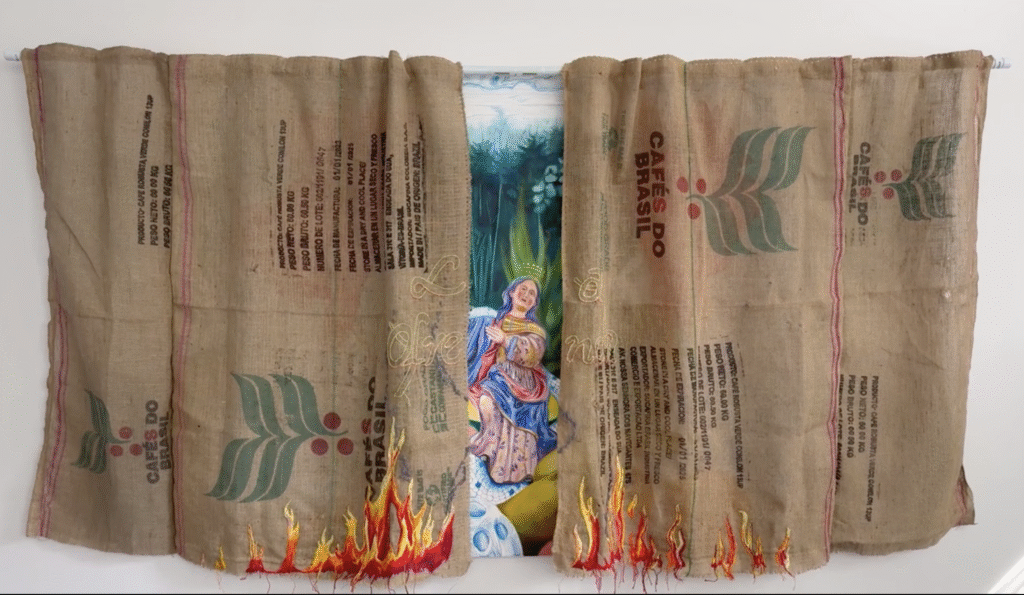

What’s most striking about Justyna’s work is her command of medium. She embroiders flames straight through canvas, lets crocheted chain links pool onto the floor, and stitches flowers, birds, and even the occasional unapologetic body part into the surface. Glass beads, ceramics, lacework, and hand-done embroidery all appear in her pieces, blurring the line between painting and textile. She will crochets custom frames around the perimeter of her canvases, turning the edges into part of the narrative. For her sold-out 2024 exhibition at La Cometa during Untitled, she even created a mechanized burlap curtain flames licking along the bottom that opened by remote control to reveal a hidden painting behind it. Her practice has earned international attention: she has been featured in ELLE Magazine, her works are held in museum collections in Poland, and she has exhibited across Colombia, Mexico, Miami, Texas, Atlanta, Kraków San Francisco, Warsaw, Oregon, Berlin, and Sydney, Australia.

Fresh off her immersive “Living Spaces” solo show at Galería La Cometa in Miami, where oversized figures and exotic flora unpacked a lingering grip. She mingled in the crowd, shrouded in a silk scarf over her face, just like her characters in the paintings. From childhood to confronting Slavic roots in a global fight for freedom, you will feel the heat in her story. Buckle up as she unpacks for us the fuel behind her work.

La Ofrenda oil on canvas, embroidery costales 54″ x 66″

DP- Your colorful paintings stand in stark contrast to the “monochrome and melancholy” art you were taught in Poland. What inspired you to embrace vivid color as a form of subversion?

JK- It wasn’t only the monochrome, melancholy art I was taught at the Academy of Fine Arts — those muted tones also colored most of daily life in Poland. The homogeneity of that grayness pushed me to search for something more alive, something that reflected my own spirit. I was a joyful child, largely unaware of the scarcity and oppression of Soviet regime surrounding me. With only eight crayons, I built my own inner world of color and imagination. Those colors became a language — one that evolved profoundly after I visited the Stutthof death camp at the age of eight. From that moment, color was no longer just play; it became a way to reclaim joy, to subvert despair, and to insist on life.

“The Animal” 2021

DP- Your work critiques colonialism and gentrification, while your heritage connects to Slavic histories of domination. How do you weave this into your art?

JK- My awareness of colonialism doesn’t come only from studying global histories, it’s also rooted in my own heritage. Poland and the broader Slavic world have long lived under the shadow of empires that sought to dominate, silence, or “civilize” them. That legacy of cultural erasure and forced assimilation shapes how I perceive modern forms of domination, especially gentrification.

In my work, I merge symbols of Slavic folk tradition — floral motifs, lace patterns, crochet, embroidery and traditional (also for many other cultures) blue and white china — with materials that suggest luxury or excess: rich silk materials, genuine gold leaf, and luxurious colors, often in the form of genuine pigments like lapis lazuli, cinnabar or cobalts. This collision between the humble and the hyper-aesthetic mirrors the process by which marginalized cultures everywhere are stripped of context and sold back as “authentic” or “exotic.” Think about the fashion industry and their use of Eastern European ethnic dress.

What connects the Slavic story to the global one is the shared experience of being seen through the lens of “otherness.” Whether in Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia, or the Americas, entire communities have endured the same cycle of exploitation — first their labor and identity extracted by empires, then their symbols repackaged by markets. By weaving Slavic motifs into critiques of colonialism and gentrification, I want to show that these histories are not parallel but intertwined — that the forces which once divided continents now operate in our cities, reshaping neighborhoods and identities alike. For me, color and irony become acts of reclamation: a way to transform histories of suppression into visual exuberance, to insist that what was once marginalized can radiate its own power and joy

Perros de Guerra 2024

DP- Can you walk us through a specific painting where Baroque aesthetics collide with pop culture?

JK- I’m drawn to the Baroque because it was all about excess — a theatrical way of asserting power and divine order. Popular culture, in its own way, does the same thing today: it dazzles, seduces, and sells us belonging through spectacle. By blending the two, I’m exploring that shared language of seduction — and also mocking it a little. One piece that really captures that fusion is Winged Victory of Miami. At first, it looks like a Baroque fresco — clouds, cherubs, dramatic gestures, flowing drapery — but instead of a divine vision, the centerpiece is a pastel-pink Lamborghini with angel wings.

The car becomes a kind of new-age chariot, worshipped by cupids as if it were a saint or a god. That’s where the irony lives. The painting borrows the visual language of the Baroque — theatrical composition, celestial lighting, sensual abundance — but instead of glorifying faith or monarchy, it celebrates something far more contemporary: luxury, aspiration, and excess. The Miami license plate is the punchline. It’s heaven remixed through pop culture, where consumerism replaces transcendence.

I’m fascinated by how both Baroque art and mass culture use spectacle to seduce — one promised salvation, the other promises status. By combining them, I’m questioning what we worship now, and how desire, beauty, and power continue to perform the same dance, just in different costumes

Winged Victory in Miami 2021

I think my fascination with the Baroque started in childhood. Growing up in Poland, color was scarce — everything outside felt gray and restrained — but the churches were another world. Their gilded altars, painted ceilings, and glowing saints felt almost unreal to me, like portals into emotion and excess.

Later, when I began painting, I realized that Baroque drama — its light, movement, and theatrical emotion — could hold the same tension I feel between beauty and absurdity. It adds a layer of grandeur and longing to my work, turning everyday desires into modern altarpieces where devotion and irony coexist

Landscape and Memories 2024

DP- You integrate painting and textiles in ways that “entangle stories.” How did that begin?

JK- It began from necessity. Behind the Iron Curtain, materials were scarce, so I used what I could find, threads, scraps, yarn. My grandmother taught me embroidery and crochet. Later, I realized how much that shaped my visual language.

Painting and textiles share the same foundation: fabric. Even in Latin, “pictura” refers to both. The needle piercing the surface and the brush adding color come from the same impulse. Textiles have long been tied to domesticity and dismissed as craft when women do it. Using textiles is my way of reclaiming that language. Soft materials can address hard truths, and the contrast can make the message stronger.

Bloodlands 2024

DP- You’ve said that it’s the artist’s role to “push the boundaries of what is acceptable” what boundary did you most intentionally provoke, and how have viewer reactions reinforce or challenge your intent to celebrate change?

JK- The boundary I most consciously explore in this works is how personal and collective histories intersect. I painted myself in the role of an enslaved person—not to compare experiences, but to acknowledge how the language and history of subjugation have shaped my own heritage. The very word Slav comes from the Byzantine Greek sclavós and Latin sclavus, once used to describe captive Slavic people. This history, though often forgotten, forms part of a larger human story of domination and liberation.

In the painting (The Feast), I wanted to reflect on these intertwined struggles for freedom. The Emancipation Proclamation in the United States (1863) and the abolition of serfdom in Polish territories (1864) happened almost simultaneously on different continents. Later, women gained the right to vote in Poland in 1918 and in the United States in 1920—another reminder that progress, though uneven, is shared. The work also brings together elements from my surroundings: the house of Mariah Brown, a Bahamian-born woman who settled in Coconut Grove after emancipation and built one of the first Black-owned homes there, and a tree from Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, where I sketch every Sunday.

These motifs connect my own past with the landscape and history around me. Ultimately, the painting isn’t about comparing suffering—it’s about continuity, empathy, and shared humanity. Our histories overlap more than we realize, and when we speak of them together, we resist division and reclaim understanding.

“The Feast” oil on canvas, crochet sculptures, embroidery 60″ x 96″ 2024

DP- What was the “Genius Visa” journey like, and how did it reshape your perception of Western culture?

JK- Art has taken me on journeys I could never have imagined, and receiving the U.S. Green Card for Extraordinary Ability in 2018 was one of them. The process was complicated, expensive, and, in many ways, traumatic. Going through endless verifications and tests made me think about what people have endured for generations to build better lives here.

Some of my relatives left Poland for America in 1906—I don’t know what became of them, but I hope they made it. That thought connected me deeply to the long story of migration. Before coming here, my vision of America was shaped entirely by television. From Poland, especially post-Soviet Poland, it looked like a place of glamour, abundance, and possibility. My early paintings reflected that fascination—the allure of the “bigger and better.” But living here changed that image.

California revealed a different kind of beauty: vast nature, space, and freedom of expression. Later, Miami showed me extraordinary diversity—languages, histories, cultures all intersecting, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes tensely. It reminded me of pre-war Poland, once a vibrant mix of ethnicities and religions before that richness was destroyed.

Here, the tropical landscape and openness contrast with the heavy historical memory I grew up with. There are no streets named after victims, no constant reminders of loss. That absence of martyrology reshaped my gaze. It allowed me to explore Western culture from a non-Western perspective—one that recognizes both privilege and impermanence, glamour and fragility. Without this journey, I wouldn’t be painting what I paint now,

Partitions 2024

DP- Your personified animals and your beloved Charlie Brown often appear in your work. How have they evolved?

JK- Animals have long been mirrors of human nature. Mischievous, greedy, impulsive. The singerie tradition used monkeys to satirize humanity. I draw on that. In my canvases, animals (and my dog Charlie Brown) act as stand-ins for contradictions. We think we’re rational, above instincts, but we’re not.

In early Warsaw exhibitions, the animals were more decorative. Over time, they gained deeper meaning. The animal kingdom isn’t far from us; desire, impulse, greed are mirrored there. Charlie Brown appears as a personal signature and a reminder that I’m not outside the world; I am in it. By placing myself and him in the mix, I acknowledge that I participate in the spectacle. The animals are metaphors and companions. They expose folly, excess, and vulnerability.

DP- What personal experiences from your Polish background have given you the courage to confront themes of slavery and colonialism in your work, and how do you navigate the emotional weight of sharing such raw, firsthand perspectives with American audiences?

Growing up in Poland, I was shaped by a history that is both complex and often overlooked. The very word “Slav” comes from the Byzantine Greek sclavós and Latin sclavus, terms historically used to describe captive Slavic people. This is a reminder that oppression, domination, and resilience are deeply woven into our shared human story. My own childhood was marked by the legacy of these histories: I was born in Soviet-occupied Poland, where travel was restricted, food and opportunities were scarce, and daily life carried the quiet weight of surveillance and control. Over centuries, Poland had been invaded, partitioned, and colonized by empires and neighbors alike, and these experiences left an imprint on the national consciousness that is still palpable today.

When Poland transitioned to democracy, the country faced enormous challenges, grappling with its own history and the sudden demands of modernization. In that context, there was little space to dwell on our collective trauma—the world had moved forward, and we had to catch up. It was only after moving to America that I began to see how these experiences connected with broader histories of colonialism and oppression. I also noticed how often Eastern Europe is absent from conversations about these themes, despite representing 300 million people. Their stories are no less important.

Confronting these subjects in my work is both a responsibility and an emotional journey. It requires acknowledging the weight of history while creating space for dialogue that is inclusive and empathetic, not accusatory. My personal experiences—of systemic scarcity, constrained freedom, and later navigating perceptions in America—inform this perspective. They give me the courage to explore these topics honestly, while also inviting audiences to consider the interconnectedness of histories of oppression, resilience, and representation around the world

El Pirata oil and 3D embroidered flames, 60″ x 60

As Justyna wraps up her reflections, it’s clear she’s not done shaking the table. She crochets through paint like she’s mending time itself. She threads discord, and she pulls color out of catastrophe. Justyna is just beginning to accelerate, leaving behind a trail of gold leaf, laughter, and warnings wrapped in beauty. Take a closer look because every loop is resistant, every toile background tells the true story, stitched, layered, and impossible to ignore, because every thread she pulls reveals a truth only someone forged by experience -and fearless enough to name it, could bring into the light.