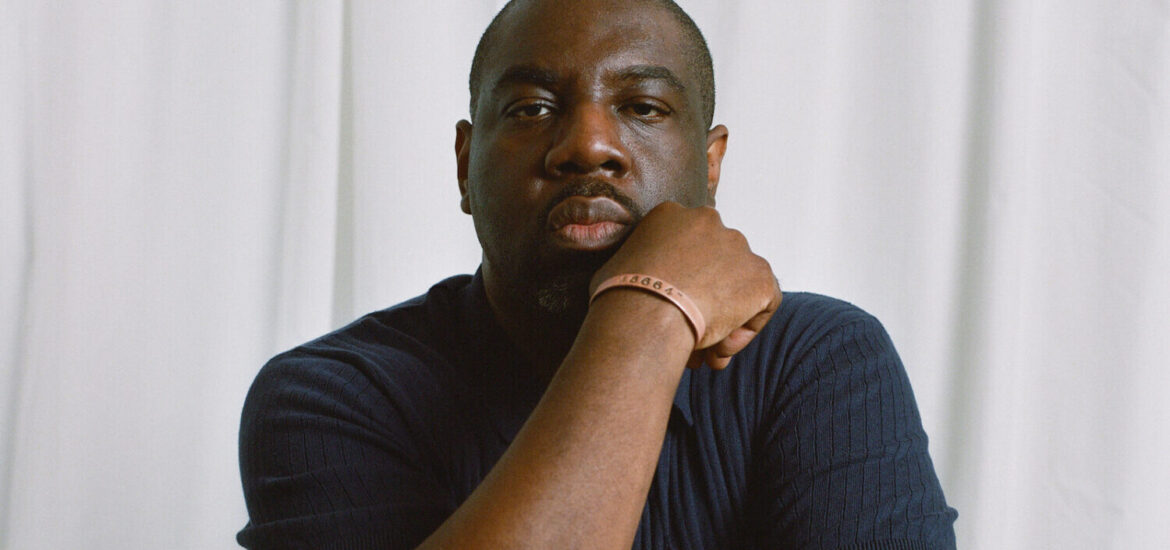

In the vast tapestry of existence, every man is born with a unique purpose, a destined thread intricately woven into the fabric of his journey. Stephen Towns journey resonates with profound cause and effect, leaving an indelible mark on both society and within the layers of his art, a spiritual connection unfolds, compelling you to linger a little longer and delve into the intricacies of his truth. In the vast landscape of art, where some pieces merely exist, his creations possess a gravitational pull.

Stephen Towns masterful command of color and form creates a visual symphony that transcends the ordinary, inviting viewers into a world where every brushstroke carries the weight of history and the resilience of the human spirit. His work is not just a representation; it’s a revival, a spark that honors forgotten souls and grants them the dignity they were denied.

Engaging in a conversation with the artist reveals a man of bravery and purpose. Stephen’s journey, marked by loss, relocation, and self-discovery, is a testament to his courage. Leaving behind the familiar in South Carolina during the economic downturn of 2008, he embarked on an unexpected path, seeking a future that resonated with his artistic aspirations. It was a courageous act, a departure from the norm, and a decision that ultimately shaped the trajectory of his artistic career.

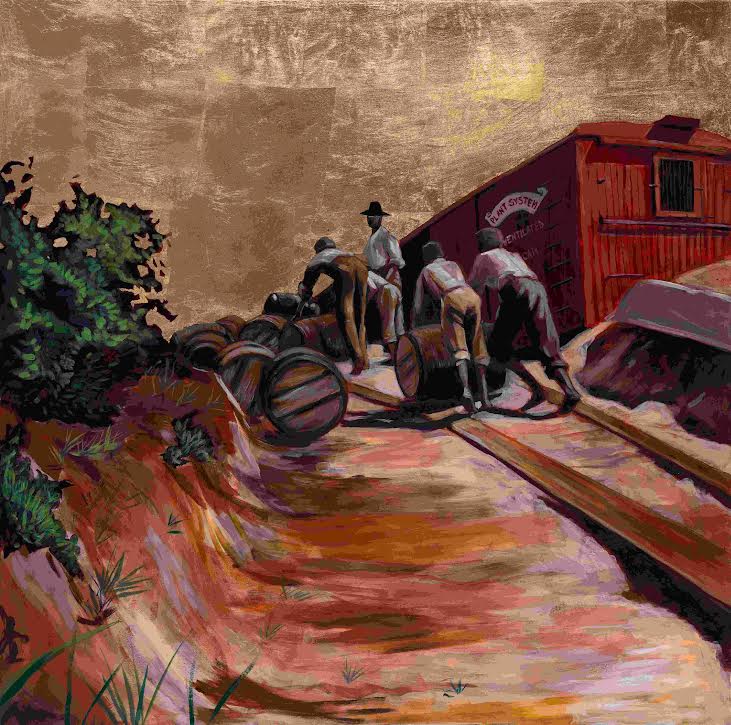

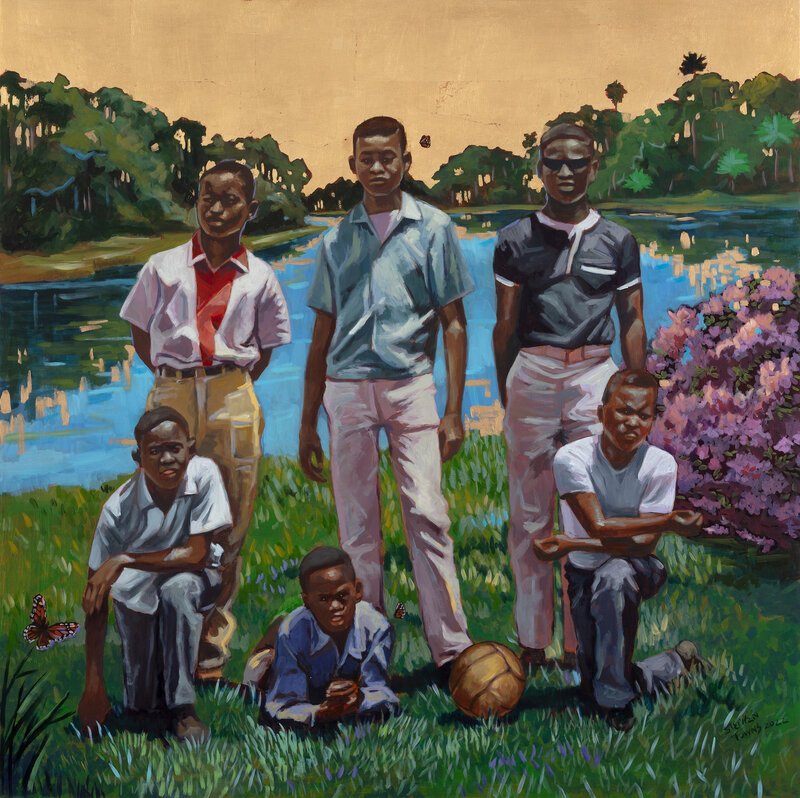

On the Hill 2021 36inx36in Acrylic, Oil, Metal Leaf on Panel Photo: DeBuck Gallery

Towns infuses his experience as a black, gay man in America to shed light on the struggles and triumphs of individuals and communities historically marginalized or overlooked from actual old photographs with vitality and spirit, confronting brutal truths and inviting viewers to engage with the narratives and emotions his art evokes.

Through a conversation that spanned nearly two hours, Stephen shared insights into the complexities of capitalism, the ebb, and flow of life, and the importance of embracing disruption for artistic fervor. The calm, he emphasized, is often the precursor to stagnation; it’s in the turbulence that true artistry finds its rhythm.

Stephen Towns art is not just about aesthetic beauty; it’s a profound exploration of societal patterns, a narrative woven into the fabric of each painting. His deep dive into history, recognizing repetitive cycles, compelled him to take action. “Capitalism is Complex” he stated, and understanding its nuances requires a keen examination of the gaps that perpetuate injustice. Stephen, with his art, endeavors to bridge those gaps and instigate necessary corrections.

Born into a family of 11 children in South Carolina, Stephen found solace in art early on. Drawing became his language, his medium of expression, encouraged by those around him.

After earning a BFA in Studio Art from the McMaster College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina, he honed his skills as a community artist, fiber artist and figurative painter.

“I came to Baltimore from South Carolina. I lost my job. I was working at a Medical University in 2008 during the economic crisis. There were no jobs to be had in South Carolina. I finally got a job at the Maryland Institute College of Art. I saw that things were bad in South Carolina, but things were bad or sometimes worse here, and I wanted to understand the background of all the injustices in American history. You may have been to Baltimore, but I like Baltimore because it was at the ground point of so much, there are wealthy people, there are working class people and I wanted to learn more about that history.” and he embarked on a mission to use art to address complex social issues and amplify marginalized voices.”

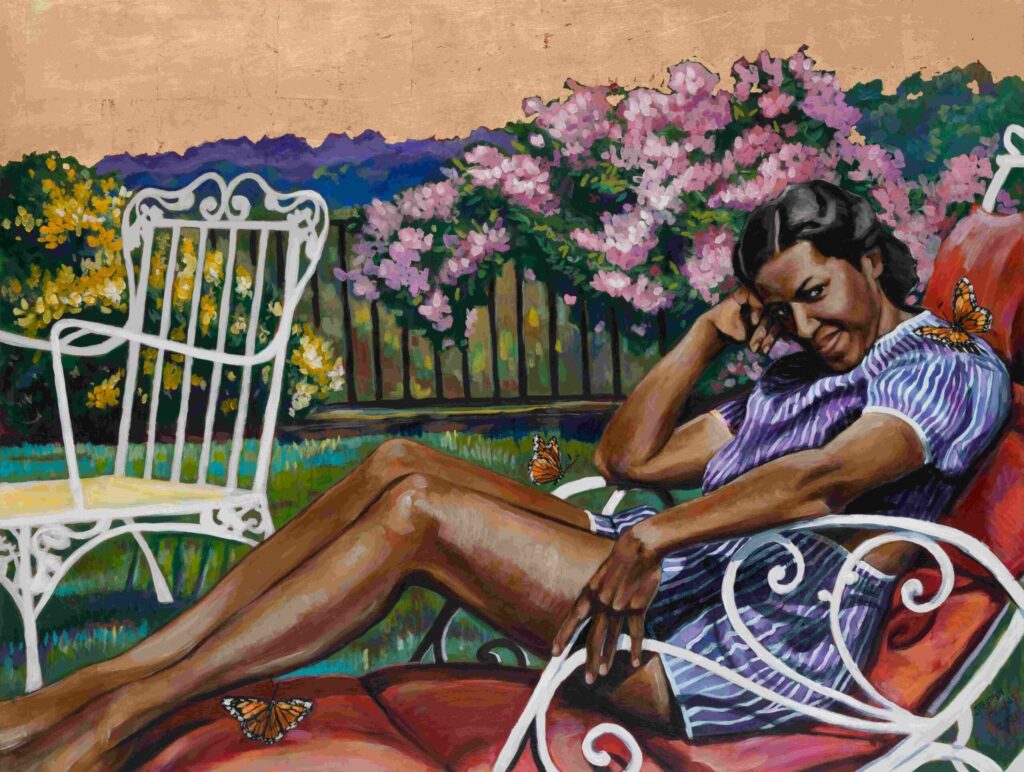

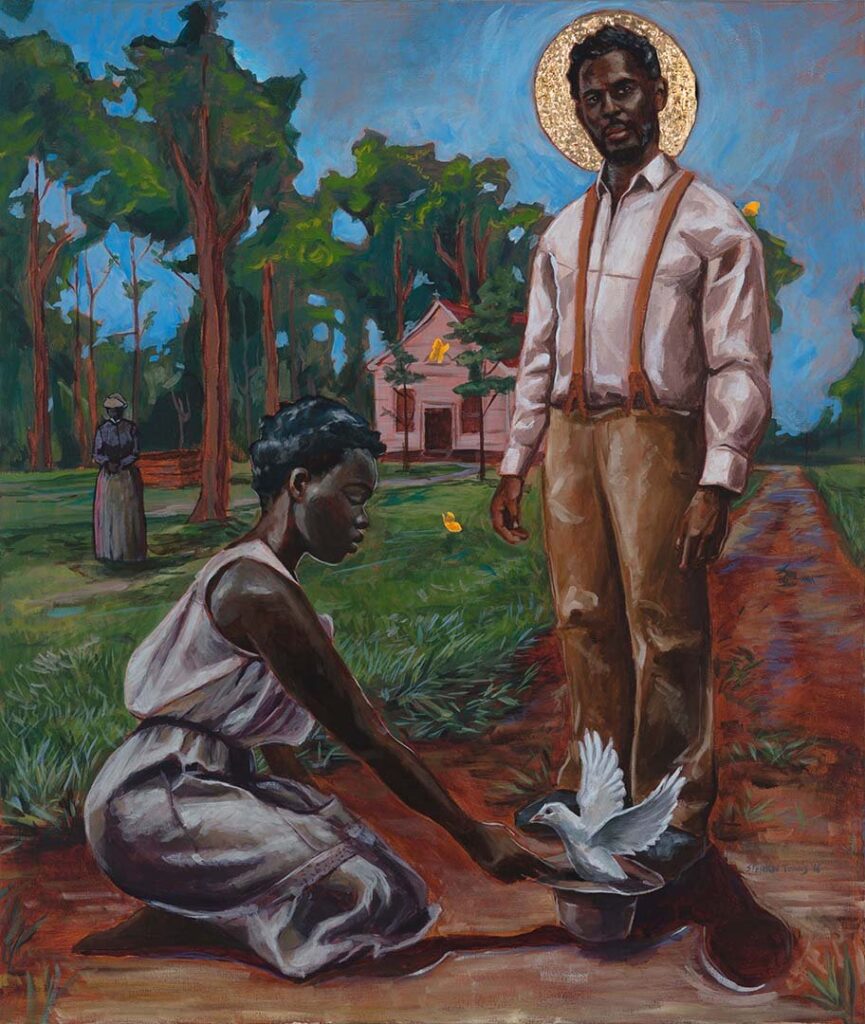

Elsie Henderson 2021 Acrylic, oil Metal Leaf on panel. Photo: DeBuck Gallery

Beyond his visual art, Towns has also been deeply involved in community engagement and arts education, working to inspire and mentor aspiring artists, particularly in underserved communities. He has collaborated with local organizations and institutions to create public art installations and murals that celebrate diverse communities’ cultural heritage, fostering a sense of pride and empowerment among residents.

“We do need laborers, people to serve people; having worked in these jobs myself, how do we treat people, and how do we not make people not feel less than us? That is the question I ask every time I make a work.”

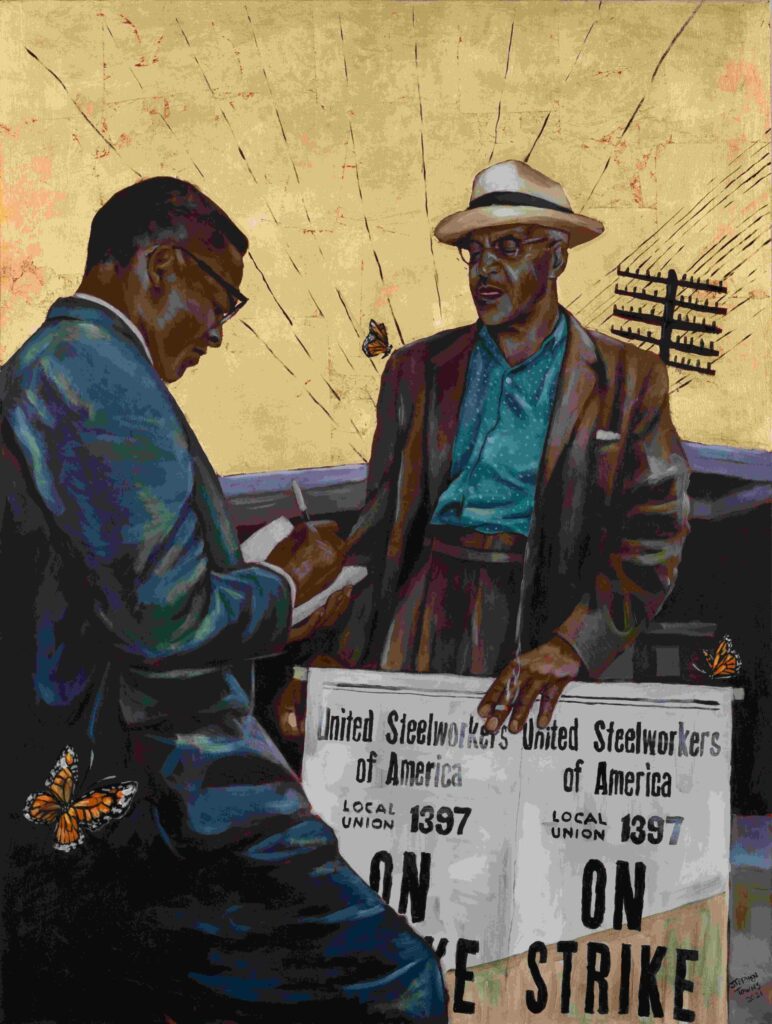

One of the series he painted was the resilient individuals toiling in coal mines, enduring segregation beyond the mines. Trapped in oppressive conditions, they were compensated with currency exclusively usable within the confines of the coal mines, preventing them from seeking opportunities elsewhere. Attempts to break free only led to swift replacement by others eagerly waiting for employment in their stead.

“It’s all forgotten so quickly. The coal companies had their own form of policing, so it was a way of keeping people captured. They would trick people from the South to come up so they would have scabs there ready to replace strikers. This injustice replicates itself in the large companies.”

Before the Dust Settles- Photo courtesy of: Sanpat collection

Through our conversation, Stephen illuminated the essence of growth, emphasizing the importance of being present, breathing, experiencing, and never forgetting who you are. His message extends to the universal quest for understanding and unity, urging individuals to evolve, appreciate, and recognize the indomitable spirit that propels us forward, despite adversities.

He draws analogies from nature, particularly butterflies, symbolizing resilience and the enduring spirit of the black community in the United States. Despite the challenges, their journey mirrors the relentless pursuit of ideals in an imperfect world. Steven eloquently narrates the interference—those few who benefit from segregation and manipulation at the cost of many.

DP- You examine history and use it as a base for your work; who do you think would be the equivalent of those historical portraits/figures today?

ST- It’s everyday people who make the small steps toward bigger change. I think that it would be people like Chris Smalls who led the Amazon workers’ strike. Hindsight is 20/20, so it can be difficult to see who the changemakers are in realtime.

DP- Do you think society today has lost a bit of appreciation for the essential worker?

ST- It’s complicated. I think there was a level of appreciation that some essential workers in medicine, education, and logistics were given during the COVID-19 epidemic–others in sanitation, fast food, and retail were not. However, many essential workers in all fields are still not compensated with livable wages. I think that we are seeing many of the holes that exist within capitalism with the number of workers’ strikes that have been occurring recently here in the US and other parts of the world. Having studied about the history of labor in America, many times it feels like history repeating itself.

The Campground at Paradise Park 2022 40×40 in Photo: DeBuck Gallery

DP- Can you tell me a little bit about your childhood and growing up with ten siblings?

ST- I was born and raised in the town of Lincolnville, South Carolina. It’s a small town outside Charleston founded by Black Americans in 1867, shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation. As the youngest, I had the advantage of not being burdened with some of the responsibilities and obligations of taking care of the household that my older siblings dealt with. We were working people living in a small four-bedroom bungalow built by my father.

I started making art at a young age. Like many kids with artistic talent, it was something most of my teachers encouraged throughout schooling. I’d always felt that art was the best way for me to communicate. I was always fascinated with drawing people and the figure. However, it wasn’t until I studied art at the University of South Carolina that I realized how to use art to explore my own identity. The themes of race and religion kept reoccurring in my work. I began questioning everything I had learned. I studied the work of artists in the area who had made a name for themselves–artists such as Tom Feelings, Tyrone Geter, Tonya Gregg, Rodgers Boykin, and Jonathan Green. Through learning about these artists, I was able to learn about the plethora of Black artists from the past, such as Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, and John Biggers. My world had opened up.

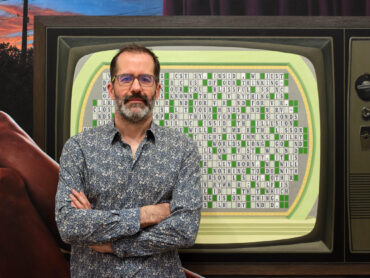

No Remembrance of Things to Come 2016 33in x 28in Acrylic, Oil, Metal Leaf on Canvas

DP- Some of your works have religious icons in them. Do you explore different theologies within them or use them purely as symbols?

ST- I grew up a Jehovah’s Witness. Though I am not one anymore, I know what it’s like to grow up with a strong sense of faith. I know the power and weakness in it.

As a young, gay, black boy in the South who did not understand what he was feeling, I always had a bit of resistance to the religion. Kingdom Halls did not have the pageantry of churches and spent a great deal of time focusing on the Apocalypse. I felt little joy going there, and it instilled a profound sense of fear and dread in me as I tried to understand the world and my place in it.

When I was in college and began experimenting with ways to understand myself within my work, I began to adopt symbols of religious iconography like gold leaf and halos to express the good in the people I was depicting. It has continued to this day.

DP- I read a story in one of your interviews where you chose to take down some of your artwork from a college exhibition, as one of the workers felt her work environment felt abusive and uncomfortable. Do you think sometimes society is too sensitive to one’s own views and neglects to consider the views, beliefs, and creeds of others?

ST- I think when you discuss issues like race, religion, or politics, you are always going to run into people who don’t agree–sometimes in the extreme. It’s their right not to. Colleges and universities, as places of learning, should anticipate it. Face it. Move through the murky discomfort and get to the other side. Even in “safe spaces,” one has to be brave. I’ve been in many “safe spaces” only to deal with the repercussions of what I’ve said or thought afterward.

The Steel Worker 2021 Acrylic, Oil Metal leaf on panel 30×40 in. Photo:: DeBuck Gallery

The college had Black staff members who were uncomfortable with some of my artworks featuring nooses being displayed in a public gallery space at their institution. The work was interpreted differently than I had intended it to be. Rather than replace the work with different pieces, I removed the work and placed tape in the space where the work had existed. I also included a statement about why the work was removed and its intended meaning. If viewers wanted to see the works, they could view images in a folder beside the display.

DP- You mentioned you listen to many spiritual books and podcasts. What have you found to be the most profound spiritual teachings in your search?

ST- I’ve listened to a lot of lectures and books by Iyanla Vansant. I would collect her CDs and tapes (when that was a thing) and listen to them on repeat whenever I was in a rut.

Probably one of the most meaningful teachings was when I discovered Byron Katie’s The Work around 2005-2006. When I read her book Loving What Is, it gave me deep insight on how my thoughts contribute to some of the pain and suffering I experience. It’s a book that I reread every couple of years to reground myself.

I am the Glory 2020. Oil Metal Leaf on panel 36×48″ Photo: DeBuck Gallery Collection of the Rockwell Museum

DP- You said in one of your interviews that the theme of your former traveling exhibition Declaration & Resistance is about people trying to make a change, exploring not only people who were able to make change but also some who tried and failed. a) Where do you think the most improvement can come from today? b) Where do you think we have created a change that maybe will be better experienced in the future?

ST- I think the most challenging obstacle currently is developing a universal understanding of American history–both good and bad. Now, it feels as if there are forces blocking access to information about the injustices that have perpetuated history. I think that in order to seek change, we have to view them honestly and develop solutions to right wrongs.

Pushing boundaries, his dedication to art as a catalyst for profound dialogue and introspection underscores the enduring influence of creativity to illuminate truths, kindle empathy, and ignite self-reflection.

In the end, the question lingers: Where do we go from here?

As we ponder the path ahead, Stephen Towns offers a profound response through his art that serves as both a reminder and an inspiration, acting as a catalyst for collective strength. In our hearts, we inherently know the path forward. It takes the strength of one to document, to remind, and to inspire many. And within our hearts, the journey begins.

He has had solo exhibitions at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, York College, Goucher College, Galerie Myrtis, as well as group exhibitions at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Jack Shainman Gallery:

Collections that his works are included: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. The Huntington Museum of Art, The Rockwell Museum, The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Westmoreland Museum of American Art, The Boise Art Museum, The Wichita Art Museum, The Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African-American Art, The Nelson Atkins Museum, the private collection of Art + Practice, artist Mark Bradford’s nonprofit based in Leimert Park, Los Angeles, as well as other private collections nationally and abroad.