It’s toasty in the studio where I am sitting with Chuck Close and Cinnamon, his adorable poodle perched on his feet. The sun is shining in the large windows, and you can hear the news on the television positioned to the right easel, beyond his brushes. Cinnamon is looking up at me, and Edie Brickell is smiling down on me like a pixilated dream, three-quarters of the way finished. We turn down the television and begin to chat. Chuck and I had met each other a few times before this.

This interview happened in parts when reflecting on it; I feel like my time with him has changed me for the better. The first thing I learned from him was when I first showed him Portray. He slowly scanned every page until closing it about ten minutes later. I was off to the side, momentarily a bundle of nerves, but in the end, I was so grateful. It wasn’t a glance, and he didn’t shove it in his bag and say, Thanks, I’ll check it out later. No one had ever done that before on the spot.

I also spoke to someone who was once waiting on a line to meet him at an event. They told me it took forever to get to the front of the line, and when they got closer, they realized it was because he was paying attention to every single person who approached him, showing interest, looking at their work, and taking time with everyone. It wasn’t a grip and grin for the web. It was a genuine interaction.

Photograph courtesy of: Chuck Close Studio

“You can achieve great things if you get working.”

For some reason, when I think of Chuck Close, I visualize him in colors. (Albeit my task is with words) so, I enthusiastically convey to you just a taste of what he has contributed to the art world, besides completely turning what we thought of as “art” on its ear since the 1960s. I have the challenge of describing to you in one article how one man has contributed to the arts with reinvigoration, and genius for over six decades. How one single person has influenced our lifestyles in ways, most may not even be aware of. He is undeniably a master at his craft.

There is a collective mindset, many memorable masters have in common, no matter the period. They disrupt conventional thinking of what something “ought to be” and deflect, delineate and challenge the efficacy of what people had been steered to refer to as “definite.”

He sits on too many boards and committees to count. He is generous with his time and supports actively, “the community that had given him so much support when he needed it.” I can only launch into and most likely end this article by letting you know the true hero of this story, is, without a doubt, Mr. Close’s indomitable spirit and unwavering perseverance.

CHUCK’S TOP TIPS:

Motivators such as Zig Ziglar, John A. Shedd, and Earl Nightingale, have impressed upon us the slightest shift in perception can change everything. “I’ve never seen the end of a loaf of bread, only two beginnings,” or “A ship is safe in the harbor, but that’s not what ships are built for.” I add Mr. Close to the above, with a gem bestowed on upon us in real talk:

“Inspiration is for Amateurs”

“Inspiration is for amateurs.” He says, then elaborates to me confidently, “You can achieve great things if you get working. Artists know how it is, if you engage yourself in a process and follow it as it goes, you will get swept up in it. Sometimes, when it is overwhelming, you can just take it one square at a time, and if you sit there long enough painting, you will get it done; and its a great way to deal with boredom.” He says with a laugh.

Chuck Close Photograph by: Oswaldo Sandoval

To think about how many times he has placed himself in front of a canvas, airbrushed, or stroked a paintbrush, the endless amounts of fingerprints, shapes, mediums, paper pulp, mosaics, wood. Oh! And to only imagine the amount of brushstrokes he has put down, given there are thousands used per portrait is staggering.

Where to Begin?

I ask him if there is anything he has had to relearn after so many years? He thinks for a second, asks me to open a book on the table behind me. “Keep going,” he says as I flip the pages. “Stop.” We look down at a small wooden house. “I grew up in that house. I was an only child of two only children.” We talked about it after, and he reaffirms your past is something you have to relearn and reflect on.

Chuck was born in Monroe, Washington. When he was five, he begged his parents for an easel and paints from the Sears Catalog and got them. His dad put him in art classes and so it all began.

His childhood wasn’t carefree. When he was five, he had his tonsils out and went into anaphylactic shock, and they had to resuscitate him. He is Dyslexic, and unable to remember his times’ tables and had to deal with this way before there were diagnosis and sympathetic awareness with special concessions being made available to students. Chuck just had to work twice as hard, sitting for hours in the bathtub, memorizing information to memory that came so quickly to others.

So much of what fueled his career was spawned from overcoming challenges. One of his biggest lessons was to break things down into smaller pieces to deal with difficulty.

When he was eleven, he had nephritis and missed most of his year at school. His father died in the next room while he laid in bed. He said it was the tragedy of his life. He was advised by his teachers that he shouldn’t even think of going to college. He couldn’t add or subtract, he was advised to aim for trade school perhaps “body and fender” work. He defied (thank goodness) the ignorant opinions, and after high school he applied to a junior college in his hometown in open enrollment and began his path in visual arts. He studied at the community college, moving on to Washington University and took a summer class at Yale, where on the merit of his work, he was accepted into graduate school there.

Chuck Close Photograph by: Oswaldo Sandoval

In 1967 he came to New York City and moved to SoHo. He rented a loft and was paying $150 dollars a month in rent. His friends laughed and told him he was spending too much; they were paying around $85. His friends, to name a few, were Robert Mangold, Richard Serra, Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein. They had a great thing going. They lived in the same area of the village, they had cheap digs, similar schooling and they also had something beautiful; There is a saying, “The rising tide lifts all boats.” When everyone does well, it helps the entire industry and everyone benefits. The pack mentality took them far and it greatly helped the art world.

He tells me a story about how he and a man who was curating a show were taking a walk to get some lunch in Chinatown. The man asked him if he knew anyone that might be good for the project, and by the time they got to lunch, they had picked up about a dozen artists along the way.

Imagine that scene, unselfishly sharing their contacts or ideas. Do you think it is any coincidence, so many of them made it? He tells me back then; artists would frequent the same places, such as Max’s Kansas City. He and his friends would mostly sit in the front, and the further back you went into the restaurant, depending on the night, you would perhaps see Andy Warhol with his crew.

It was a scene that has all but disappeared. Rents today are ridiculously high for an aspiring artist in New York City. The financial ability of artists to swim in the same pool geographically is not feasible. With it, the camaraderie has lost its luster, leaving artists to clamor for themselves and along the way, the art world has become a business. Hedging artists like stocks, being singled out.

“We were hell- bent on removing every trace of standards of “normal.”

What drove them then? Rejecting notions of reform, to serve up some of the same. The same standards and uniformity. They questioned the perception and definition of what was considered “art” up until that time. If you think about it, innovation throughout time has been created by a small cluster of like-minded people who are fed up with how things are. Wanting to forge and embrace new ideas, artists including Chuck took it upon themselves to become completely unconventional, unidentifiable and incomparable. They were all consummate and all unique. “We were hell- bent on removing every trace of standards of “normal” which is anti-theoretical to appropriation” The truly talented “tweak with their instinct” and Chuck had a deep understanding of this. Being gifted with the innate ability to think on a different plane served Mr. Close well at this time.

Chuck Close Photograph by: Oswaldo Sandoval

“Clement Greenberg, an art critic at the time had said, the only thing you can’t do anymore, is paint a portrait, and I thought, huh, not that much competition!”

That Guy

Around this time, (circa 1967) He tells the story to me with a smile, “Clement Greenberg, an art critic at the time had said, the only thing you can’t do anymore, is paint a portrait, and I thought, huh, not that much competition!”His bushy brow raises above his spectacles, and his blue eyes emit a sassy, satisfied gaze as he recalls it. And so, “He” was born, or “him,” or “that guy.” In the fall, Chuck Close began his first large head. “He” was a self-portrait. Chuck has created over forty of “that guy.” “Heads” as he calls them, (even defying the word portrait). An average of nine feet tall, and all done with about two tablespoons of black paint. “Wherever you see white, simply had the absence of paint.” He would dilute black paint down to achieve the mileage. So, not only did he take Mr. Greenberg’s advice, do the antithesis and use it to his advantage- he went big.

Referrring to his paintings he says, “The bigger they are, the longer they take to walk by and harder to ignore. He created a “high impact image that could be seen from 100 yards, and if they get up close enough, it was all dissolve. I wanted them to love me, hate me, but look at me.” You cannot ignore a nine-foot head and a twenty-two foot long nude painting if you wanted to, and then, when you got close to it, it would become abstract. He wanted you to feel like “ants crawling on a sandwich.” (He still thinks twenty-two feet was too short.)

DP- When you first realized you could have something executing abstract on something realistic?

CC- “I tried to make sharp pictures and some of them came out blurry, and I thought that would be interesting. There is a way to understand the space with a face, I wanted an abstract reading contradictory to the iconography. I’m face blind, so use my working as a way to submit the image to my brain.”

DP- How do you make the transition? Do you look in each square as if it is its own universe?

CC- “Well, you don’t set out to go there. When you work, it occurs to you several ways, some are more interesting than others.”

Very few things in life will get you as far as making an excellent presentation.

You know, there are times, such as when you are staring at a nine-foot head that time stands still. You feel encompassed by it, and although it may be massive, the details are intimate, every crease, wrinkle, pimple, and you can hear yourself breathing. Then when you know these are images of his close friends and family, (and why) put to multiple mediums, they become endearing, because it is a way for him to remember them all. He suffers from face blindness, and he can only remember faces on a flat surface as opposed to seeing someone in real life.

Each head is a dedication of shared experiences, evident in his deep interest in the subjects and a testament to the power of this venerated figure. If you think about it, after he completes a painting, he knows what one looks like probably more than most else would. One must expect to consider some concessions; it is not as if the sitter sees themselves the way the camera will pick it up, and the subjects give him full reign over what he will do. There is an objective truthfulness to them. He creates something artificial based on something real and dear to his heart.

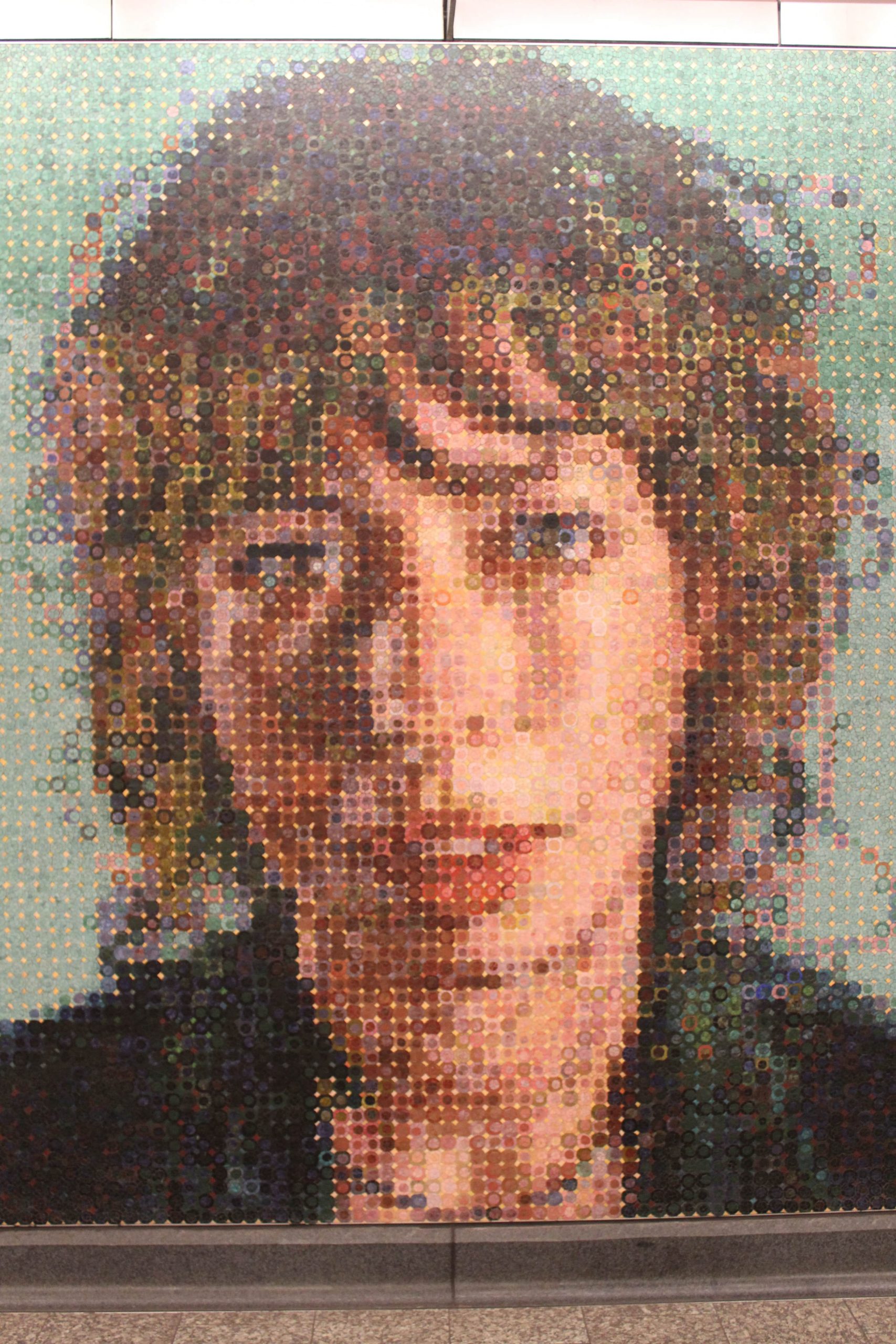

About The Mosaics

Chuck Close Mosaic Photograph by: Donnalynn Patakos

“At various times in my life I worked on mosaic-like projects. When I was an undergraduate I worked with stained glass. In 2011 I was commissioned by the MTA to create twelve mosaic versions of my portraits in the 86th Street station of the NYC subway.”

Each one different, and each one exceptional. Every hair in his beard, eyelash, and brow are unbelievably set in glass; some are stone, glass, or ceramic collectively, totaling over 2,000 square feet.

“Cecily” Mosaic in The Q Subway station, NYC Photograph courtesy of : Chuck Close Studio

“Cecily” Details Photograph by: Nafis Azad

DP- Let’s get down to the Nitty “Griddy.” How does it work?

CC- “I first take photographs of the subject with a 20×24 Polaroid camera. When the prints come out, the sitter and I have a chance to see what we have done. I never have a problem choosing the photograph I will use.” His assistant then grids the canvas. Deconstructing the image and slowly putting it back together, Chuck starts with the cyan, then adds the magenta to get a purple effect, then adds the yellow, layer by layer, square by square, starting at the top left and working his way down. ” I place three, one-colored paintings running on top of each other.”

As we sit and chat, he tells me about things that have happened to him. It is a testament to his perseverance and mindset, and despite it all, his achievements outweigh the detriments. “I don’t think I’ve thought about death for three minutes of my whole life, because I’ve been up against it. I had disease, I had, couple of heart attacks a couple of strokes. I had cancer; I don’t even remember I had cancer. A few months ago, I had been dropped on my head, and I was unresponsive for two and a half days.” Most notably, on D Day, 1988, at 48 years old, ironically the same age his father passed away, he was waiting to be called in a ceremony honoring local artists and felt a strange pain in his chest. He walked across the street to Beth Israel Hospital. He suffered a spinal artery collapse, leaving him a person with quadriplegia. He was in the hospital for eight months.

“When they told me I was in for a rough ride, I painted in the basement of the hospital.”

DP- Is there a pattern to how you work?

CC- “Every day I try to get to work about three hours in the morning and three in the afternoon- a total of six hours a day. Today I will do what I did yesterday, and if I stay in there long enough, I’ll get the work finished.”

Every day, has led to over 150 solo shows, and over 800 Group exhibitions. He has been the recipient of the National Medal of Arts from Bill Clinton. He has received over 20 honorary degrees, including Yale where he graduated. He was elected into the National Academy of Design, painted President Clinton, and photographed Barack Obama in 2012. He was appointed by Obama to the Presidents Committee on the Arts and Humanities. (refusing to photograph the current President, along with a letter of explanation). He has had shows in the creme de la creme of art halls globally: The MoMA and the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York); the Walker Art Center (Minneapolis); The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia (Madrid); The Tate (London), The Centre Pompidou (Paris), Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst (Aachen), the State Hermitage Museum (St Petersburg); the Venice Biennale (three years); the Carnegie International: White Cube (London); the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (Sydney) and the Ravenna Art Museum in Italy.

As he puts it, “I made the work and hoped it would hang up there with the best of them.” His vision, his anti-conformity, and ability to process and think differently have made him a superstar in his field. Proving that no matter what crap may come your way, get on a raincoat, rubber boots, and a big fan and go for it. Go for it every day.

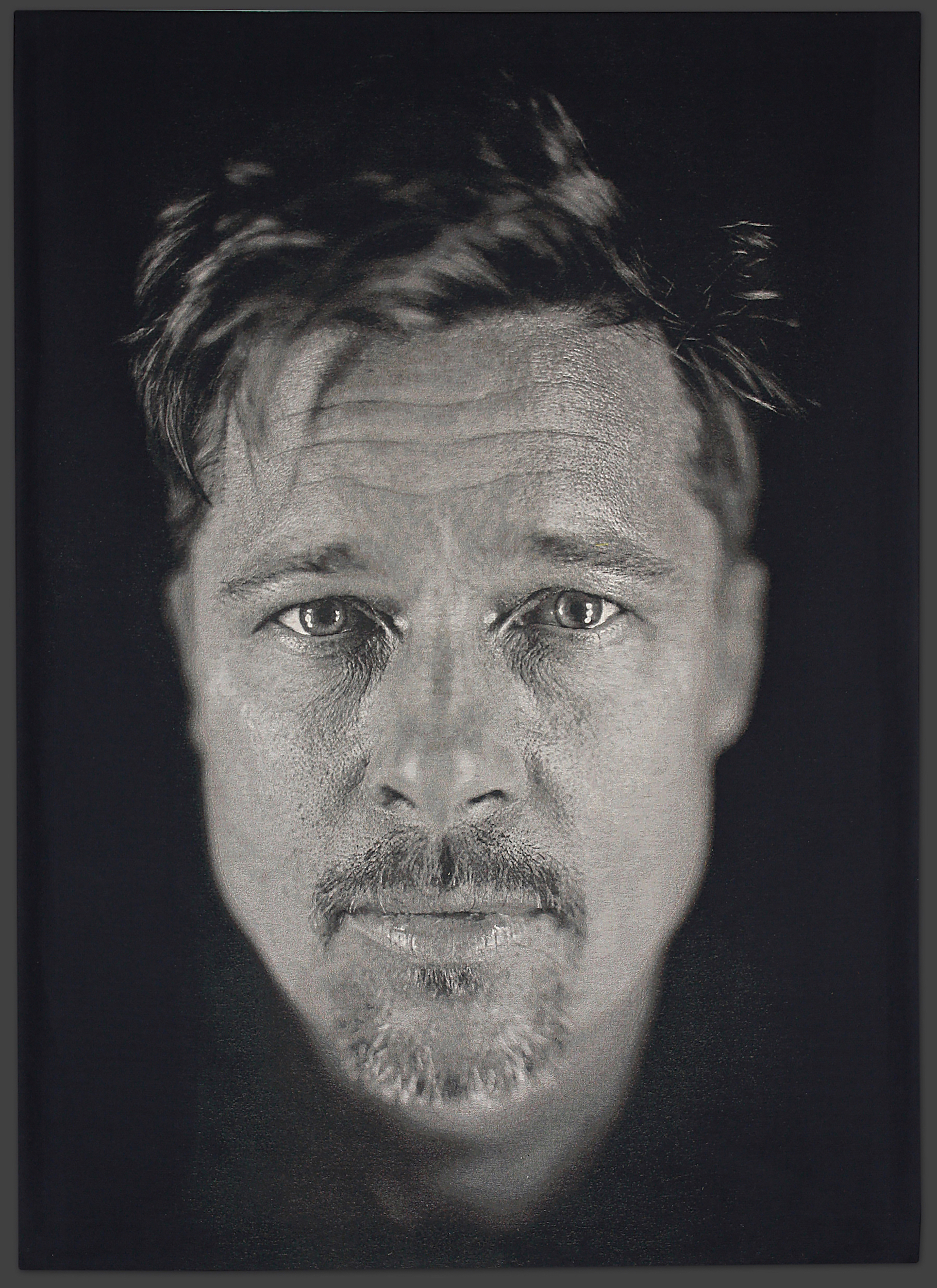

About the Tapestries

Brad Pitt Tapestry Photograph courtesy of: Chuck Close Studio

Looking at the humongous tapestry of himself and another of Brad Pitt in his studio, you wouldn’t right away know it was a tapestry at all; it is so precise. You realize when confronted with one of his works, the need to pause. I look at the back of the tapestry, amazed.

DP- What brought on the tapestries? Did you pick the fabrics and the colors?

CC- “I got the idea after having some experiments. Sol LeWitt went to China and brought me back some black and white tapestries. So, I asked if I could do the same, and he told me the name of the factory. I sent someone to China only to find out Mao had the looms destroyed.”

Mao destroyed the local looms and businesses in his effort to erase the four olds: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. So, Chuck had his tapestries woven in Belgium. He describes to me the methods used by weavers in the past. “It used to be that the weaver, usually a man, would have his children above him dropping down the threads. So, weavers eventually figured out a way of working with strips of paper with holes punched in them.”

DP- Most memorable show to you?

CC- “My exhibition, Artist’s Choice: Chuck Close, Head-On/The Modern Portrait at MoMA in 1991. Kirk Varnedoe asked me to do the show. They bought my first large painting after I got out of the hospital.

Also, my retrospective at the Whitney at 1981, which started at the Walker Art Center in 1980 then traveled to the Whitney.”

MET AND MoMA

CC- “Well, I almost did a show at the Met. I went in to see the director. They had a lunch in the director’s dining room. Everyone at the table had their own waiter standing behind them at their beck and call. The Met had offered me the last seven galleries on the top floor. So, they sent someone traveling around the world looking at every piece. Then, the director told me they had the chance to do another show, and there would be hardly any space left. So, I went back to the Met, and I told the director that I didn’t want to do the show and I went back to the MoMA and did the show there.”

DP- Do you give yourself any sort of time frame when you do things or do you take it at your leisure?

CC- “I used to work every day and make a painting a day. Now I work every day and make a painting every year. I like what I’m doing better now.”

DP- Where do you feel most connected in the world?

CC- “Geographically? In Washington State, it would rain 200 days a year there. Amherst in the two years I lived there (1965-67) were pretty good. I then realized it was water that I wanted. So, I liked Long Island. Long Beach, where I now live part of the year, is on the south side. It’s a nice town. The beaches are so much cleaner than here in Miami.”

DP- How about the place in the city?

CC- “I spent four days there last year. I am emotionally tied to my neighborhood in Manhattan. My favorite restaurants and galleries are in Manhattan, so I am still emotionally tied to it.”

Chuck Close Tapestry Photograph by: Oswaldo Sandoval

DP-What would you like to tackle in the future, artistically speaking?

CC- “Lots of things. When I see something that someone else does and it’s something I can use, I’m thrilled. You can’t invent everything, but you can make everything yours in a unique way.”

Chuck’s works are a bit reminiscent of life:

- Sometimes, with just a bit of resourcefulness, you can get more out of it than you ever thought.

- Everyone’s head is made up of different layers.

- Take it inch by inch with a plan, and you can achieve whatever it is you are working on.

- From a distance, some things may seem crystal clear, and when you get right up to it, you can’t make out a damned thing.

And as I declared earlier, when I think of Chuck, for some reason I visualize him in colors, and as my mind drifts to our talks, the things he has shared with all of us, and everything he has accomplished, I can only think: You can’t leave a rainbow behind if it has always been sunny.

Chuck Close and Donnalynn Patakos Photograph by: Oswaldo Sandoval