The day I met Erik Foss was memorable. It was one of those days you wake up and what you have intended turns into something you couldn’t have foreseen, and best of all, as an added boon, I made a new friend that day. Looking back, it reminds me of an art version of Ferris Beulers Day off, you know that line when Sloane asks Ferris, “What Are We Going To Do?” and he responds: The Question Isn’t ‘What Are We Going To Do?’ The Question Is ‘What Aren’t We Going To Do?'”

Let me rewind. Upon arrival at Erik’s studio, late morning, I slowly make my way up the stairs. The railings were cold on my palms, counterbalancing the burn in my thighs. It was like doing a real-life Stair-Master with four-inch heels and feet longer than the steps. Mindfully, I try and mute the heavy “Clomp, clomp,” advertising our arrival to the building, ricocheting off the walls within the hollow opening above and below. Quickly, I glance down behind me. Unbeknownst to him, the collector a few steps behind motivates me to keep going. Partly out of pride and partly out of worry, I’d fall on him. (I definitely wore the wrong shoes.) We make no eye contact; he is watching his feet as he steps up, and I cheer with a chuckle, “Come on, Mr. Lee, we can do it!” Six flights up. I had not met Erik Foss yet, and images of bringing large canvases and bags of groceries regularly up and down this trek fill my thoughts, and I can only imagine he will undoubtedly have solid legs.

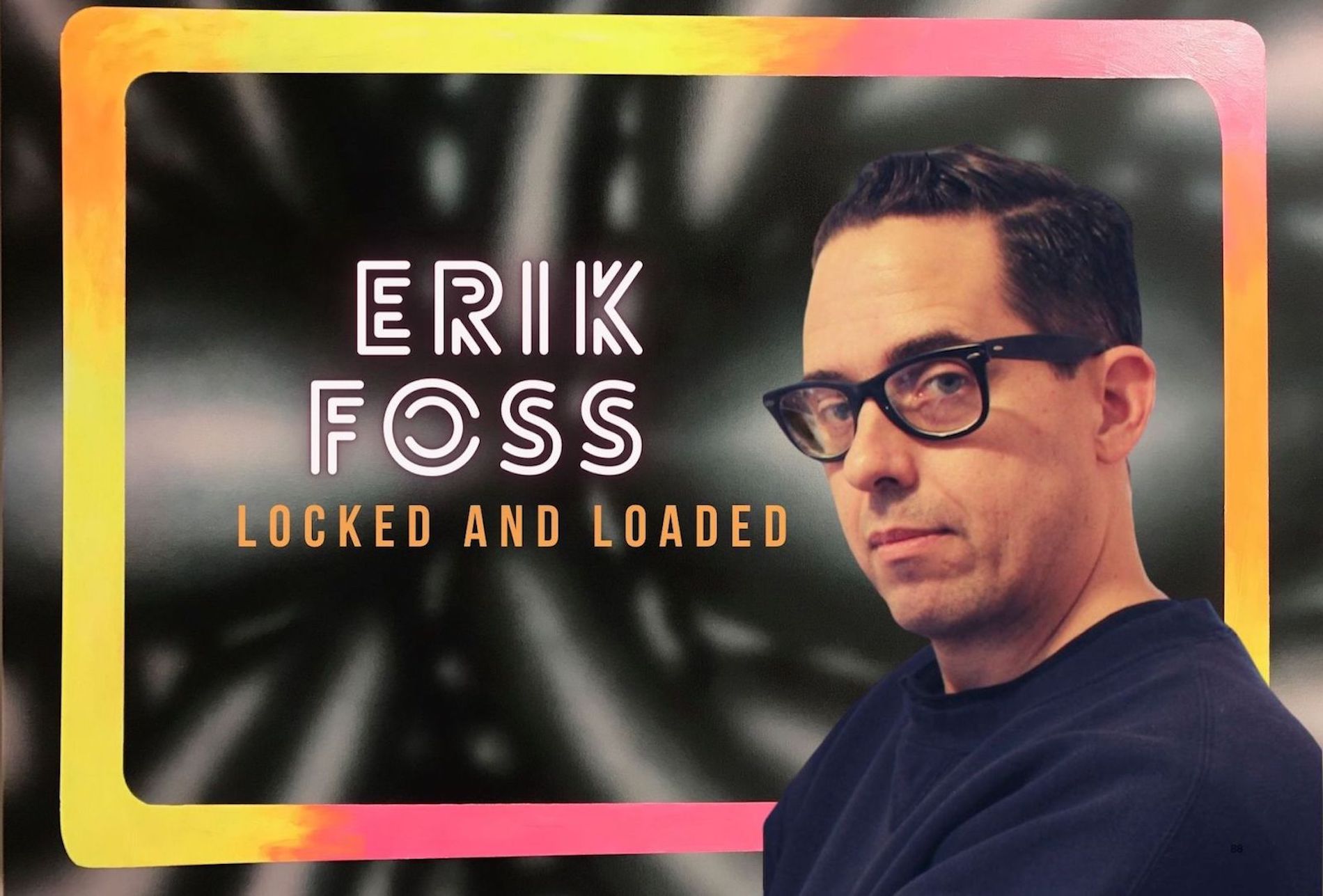

We arrive at an open door and a big warm greeting from Erik. He is tall and has a tattooed Clark Kent look. He is laidback and friendly, but it seems if you lose sight of him for a minute in a crisis, he could emerge differently as a punk version of a superhero with a leather vest and black converse. Wasting no time, Mr. Lee starts looking through the big books of photos and collage, paper works, and pen drawings.

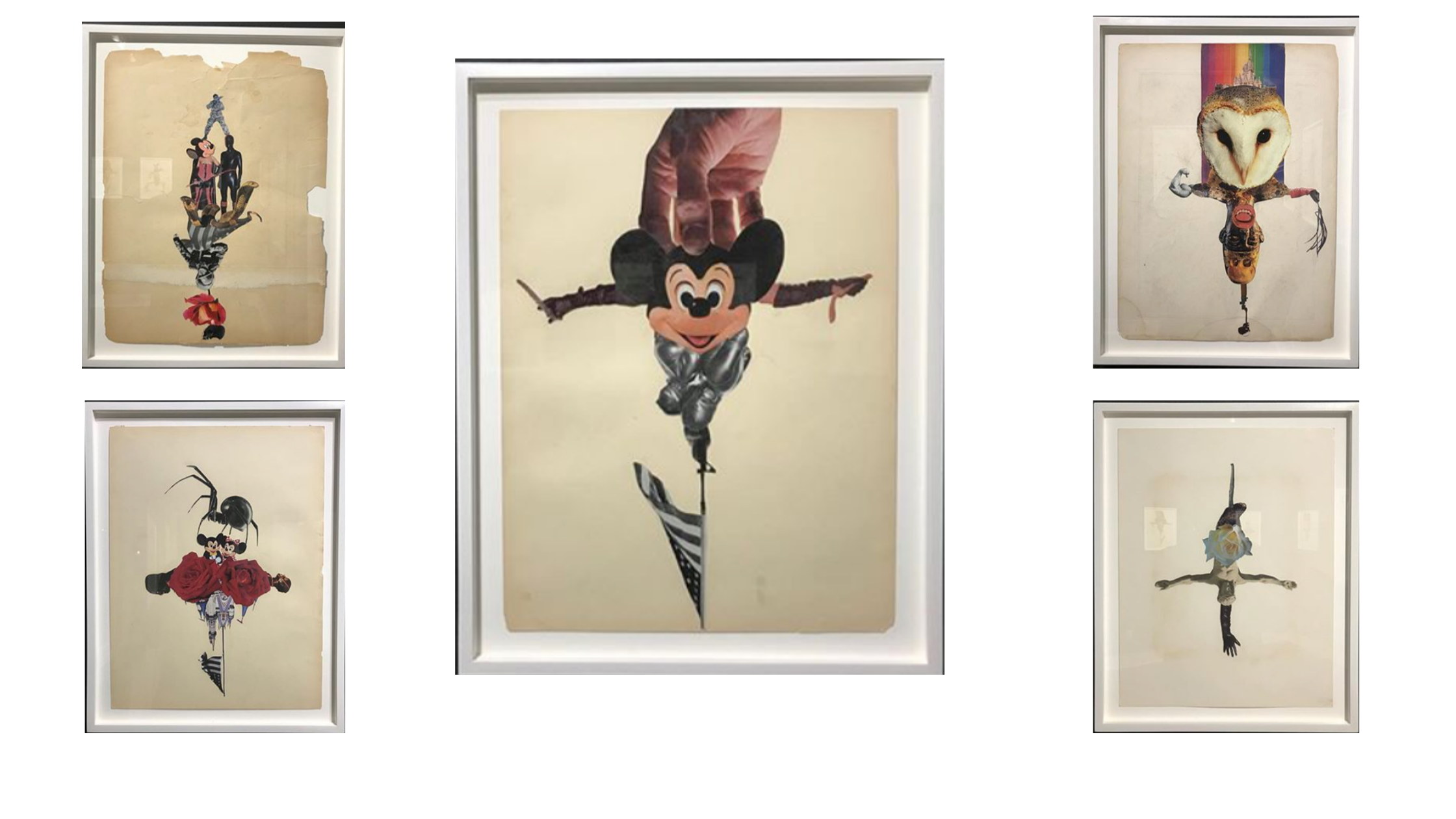

Various collage works by Erik Foss

Right or left? I ask myself and choose right and am confronted with his roommate’s black cat, guarding some works, staring me down in front of a mélange of style, thoughtfully displayed in three rooms. Each one is like entering different places in his mind. What is apparent, immediately, is a sensitivity to the human spirit’s tenebrosity, carefully documented in his photos, collages, and prominent shadows in his painted work. With white backdrops, the abstract canvases, some he calls “Dot Paintings” reveal carefully placed leaden patches of color, sometimes sparse, or veiled, all consistently winsome.

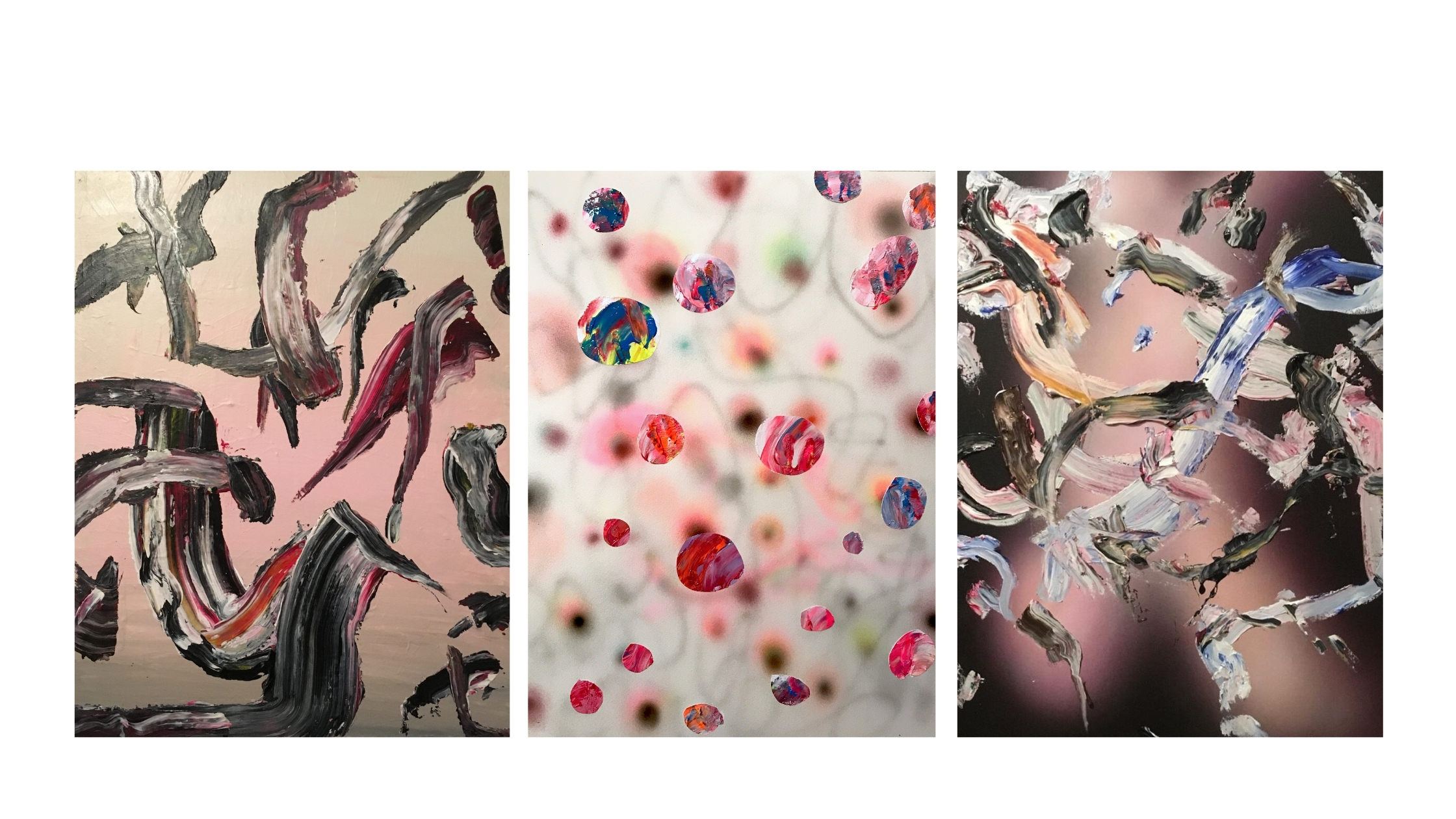

“ pleasure treasure “, Middle, “Srebrenica” available on Portray’s Exclusive Gallery,

Portal Paintings

His coveted “Portal” paintings are there; The one we are picking up sits prominently displayed with its diaphanous background just beyond sharply “floating” oil stick rainbows, which create an entrance into the beyond. Hypnotized by the swirls of bright colors and perceptible caliginous depth, I let out a small “Oooo!” He airbrushes all the backgrounds in the portal paintings. At first glance, one may assume they are digital, giving kudos to his artistic ability. Experientially, he tells me he would like the viewer to see what it may feel like to drop acid. I laugh. (he means it) we laugh again.

Portal Paintings by Erik Foss

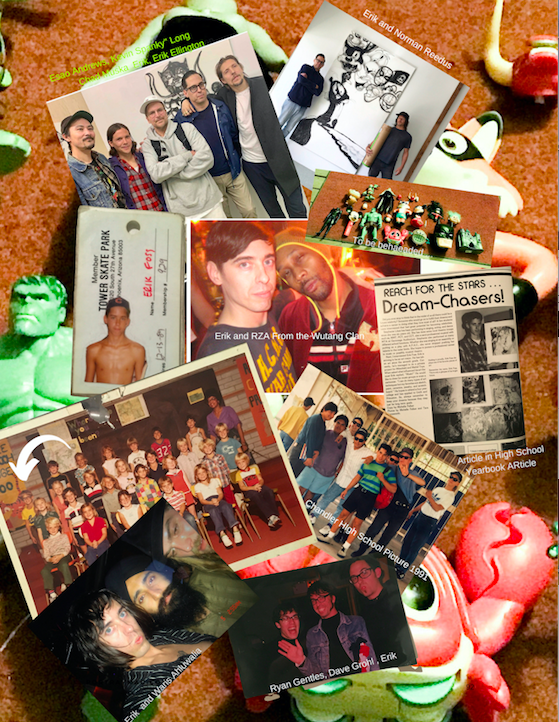

This break-out artist is no stranger to the art world. Erik has been in NYC since 1996. Having been the co-owner of “Lit Lounge,” he is part of the neighborhood’s art history. He and his partner signed the lease in late August 2001, just days before 9/11. They had just started construction when “it” happened.

Erik recalls the first mass exodus in 2001 (because here we are again) from New York City, with many fleeing as soon as the bridges and tunnels opened in their Uhaul trucks with mattresses roped on top. Foss stayed put in and worked 28 days straight forging on in the downtown 24-hour Russian diner, Odessa. Despite the desperation and chaos surrounding him, he remained steadfast. Five months later, in February 2002, Lit was open.

Patrons who had frequented it have told me it was like a modern-day Max’s Kansas City. It was straight, gay, no photos, no press, and they treated the artists as celebrities. It was in the space of the original Ratners Deli, a social club in the ’30s- 50s. Two stories, boasting a legitimate gallery in the back of the bar they aptly named “Fuse,” where there had been a fire years before in the kitchen of Ratners. Lit Lounge, with Carlo McCormick as a greeter, and Fuse hosted over 180 art shows in fifteen years. He had a solo show before Lit opened and that whole time, Erik never made a big deal about his art.

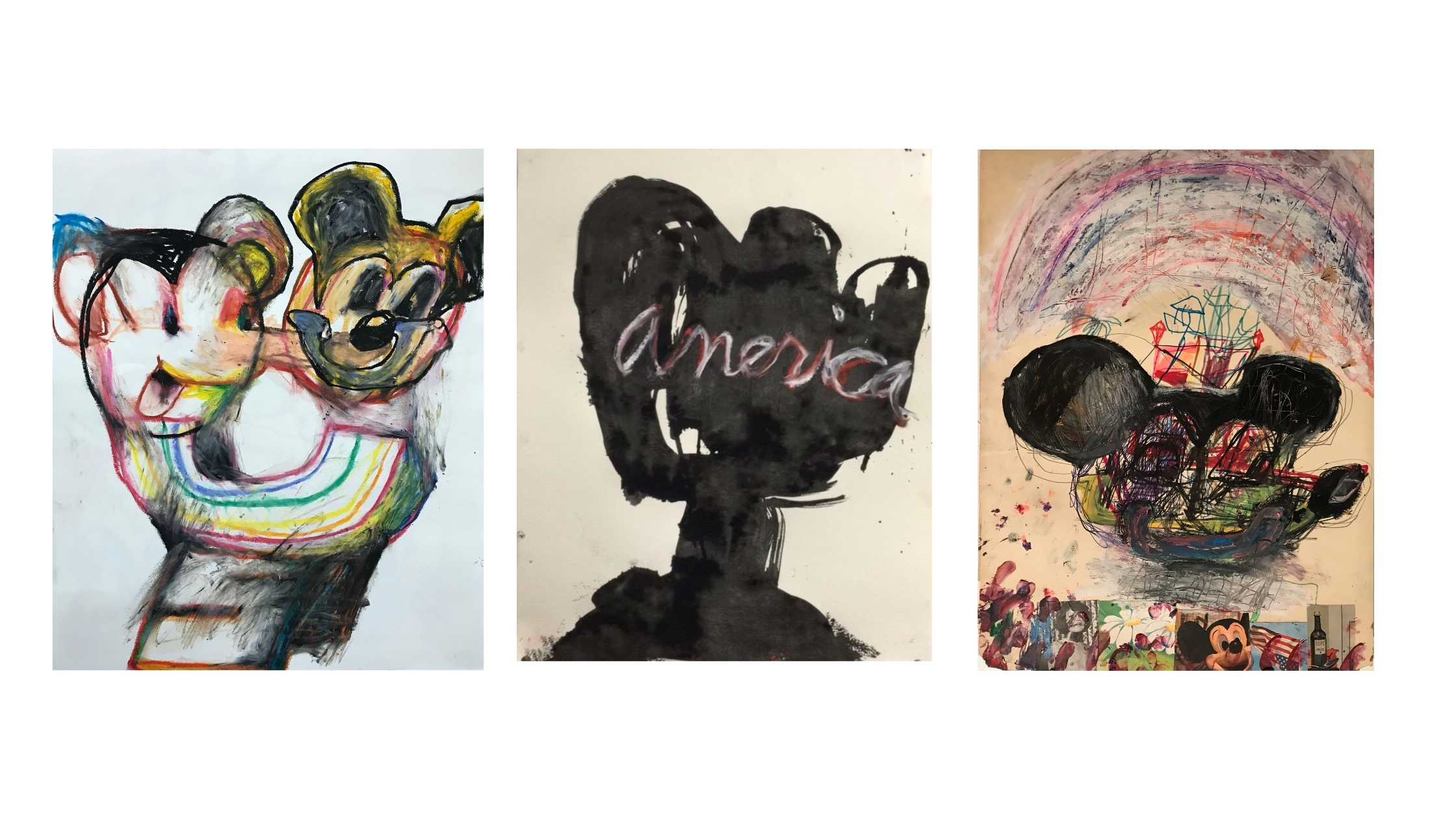

Mickey and ‘Merica

“Mickey Mouse is right up there with Coca Cola and the American Flag; it is apparent iconic imagery”

Mickey with guns?” I ask, staring at the watercolored, washed-out pastels of Mickey Mouse holding a weapon in one room of his studio. I had noticed Mickey pen drawings and collages as well in the large books. Erik clarifies. His father was a marksman, and he learned how to shoot a gun before he could ride a bike. He has been shot at and experienced someone shot and killed. In Arizona, where he grew up, everyone had a gun.

Left, “Lets have a War” 2020 Middle Artist with “Marked” and Right, “Stoners vs. Punks” 2019

EF- “My dad was a toy designer. He designed the joint mechanisms for He-Man and Masters of the Universe. This is what I grew up with. Mickey Mouse is right up there with Coca Cola and the American Flag; it is apparent iconic imagery. When I introduce these characters into my work, I’m talking about how capitalism is a pretty dark system. I’m not pointing a finger. I’d like to consider myself a patriot and love what this country is supposed to be. The system is not there yet, and what is happening now is going to decimate a lot of small businesses and poor people, and hopefully, this will change.

Mickey Drawings: Photos courtesy of the artist

“Drive in a cab, and anyone will tell you how lucky you are to be in this country. Most Americans have never been to a third world country. They have not seen true poverty and pain. We have running water. We can turn on a stove. Flip a switch, and you have electricity. We take these things for granted. We can stay at home. For an American, I have had everything taken from me. But I’ve spent time in a third- world country, and I’ve had it better than they ever have. COVID 19 has wiped out my old industry, and I am so glad to be an artist.”

Don, his dog, some rope and a skateboard

Due to his father’s love of alcohol in his youth, Erik and his twin brother would spend time at a bar called “The other Place” Erik’s father was friends with the bartender, Don. A painter and illustrator, creating posters for children’s books and airbrushed movie art in the ’80s.

DP- How did Don influence you?

EF- “Don was cool, rode a motorcycle, and had a big dog that would pull him on a skateboard. I see so much of myself in Don. He was one of the first people that told my dad that I had artistic talent.”

.

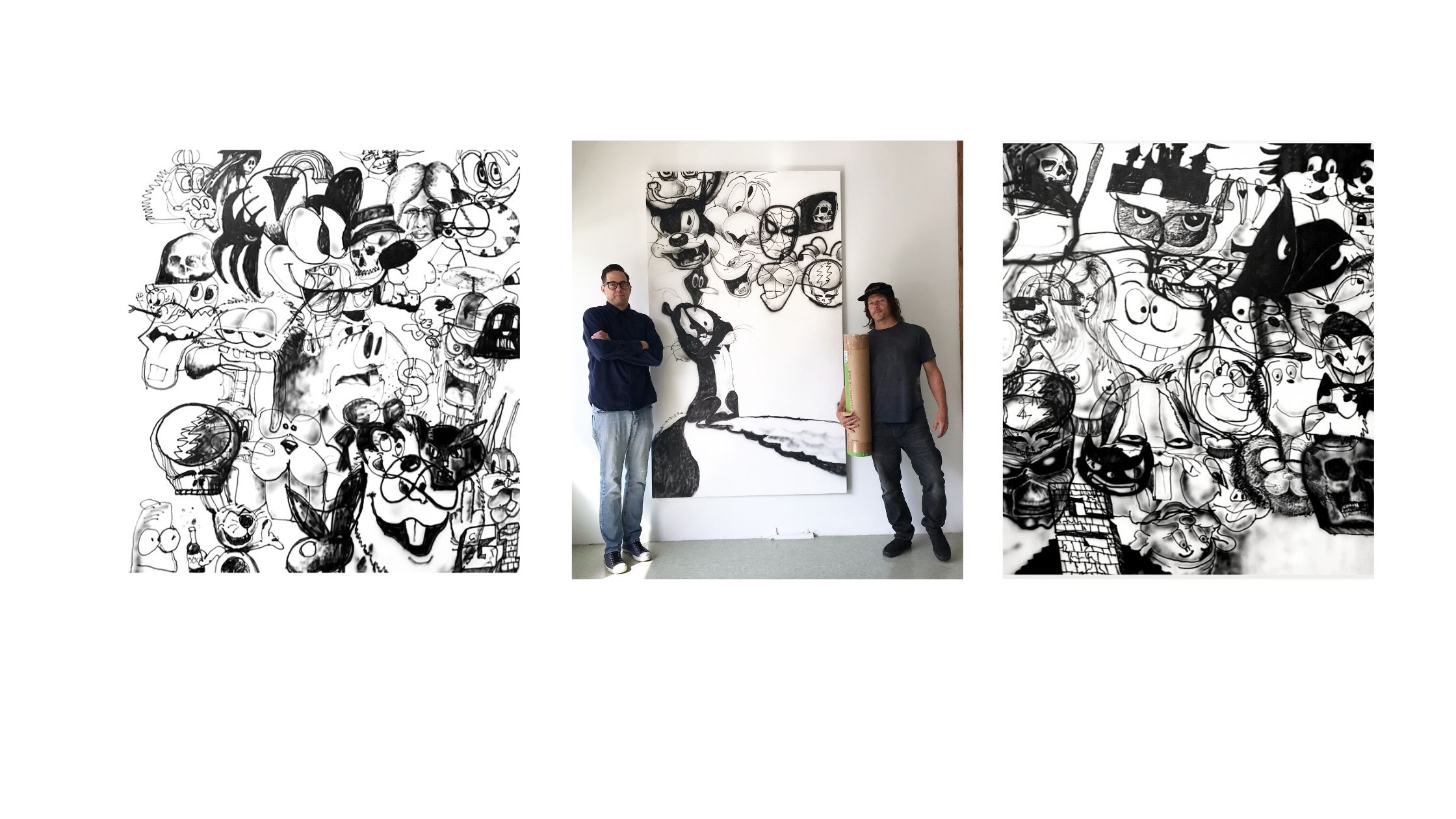

“Family Reunion”

About a year ago, while emptying the ink from the airbrush one day, Erik drew Mickey, a skull and a cat, in a totem fashion that initiated a “house party” on canvas

“Family Reunion”, Middle Erik Foss and Norman Reedus, Right- “Prime Time”

He stayed up, drawing every character he could think of one night, and he called it Family Reunion. “I thought to myself, I’m going to make a piece that is just all of my favorite things growing up, practicing drawing.”

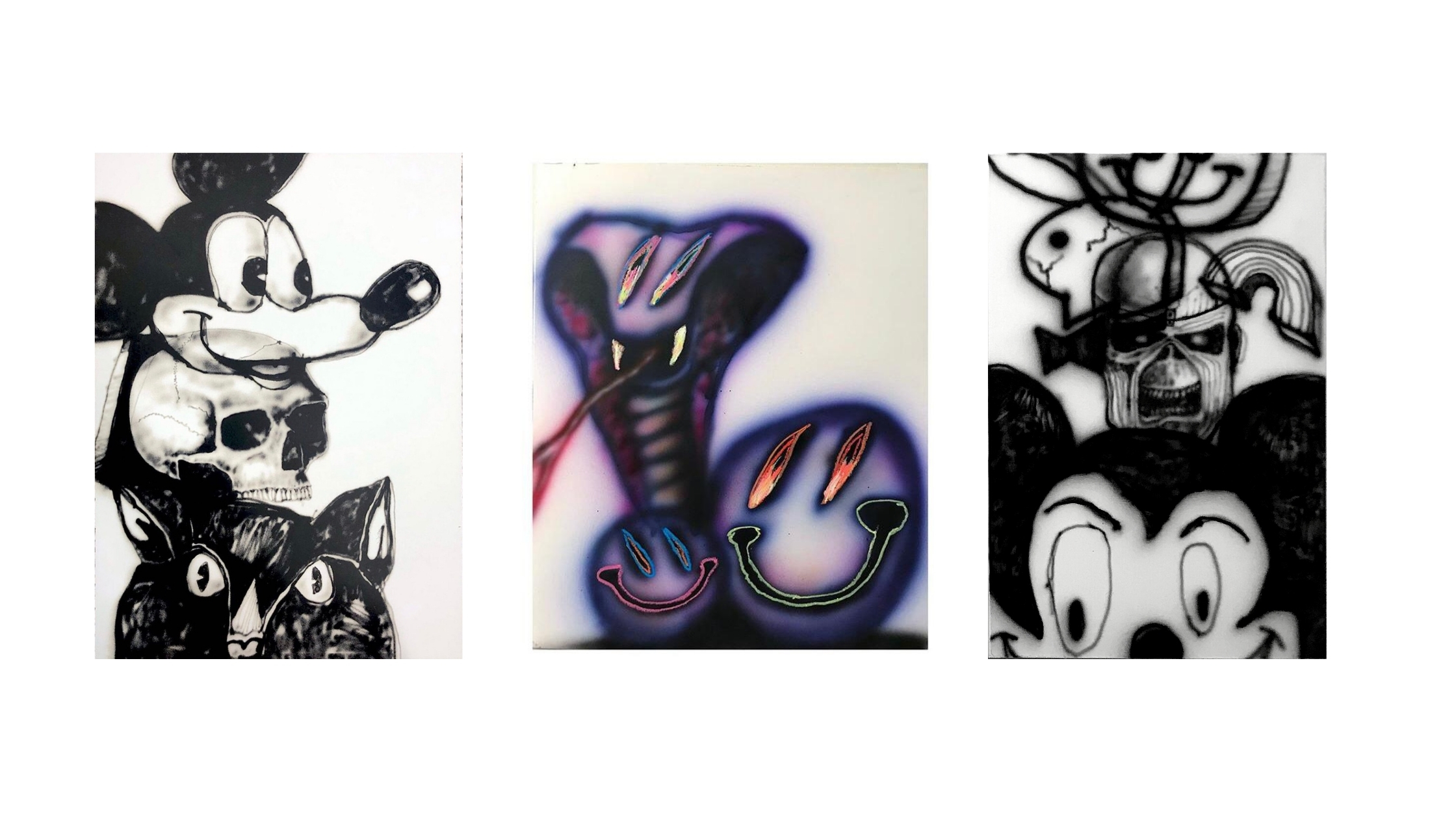

“American Classic” “Snake Smiley Drawing” and “Maiden the Shade”

American Classic (above left) was made into a print edition of seventy. Thirty-five by Popink and thirty-five by Moosey Art and sold out faster than just about any other print they have had, with people making loads of remarks and emojis of satisfaction getting one, like, “Scooped!” enthusiastic about scoring one.

Erik has recently expanded his repetoir into sculpture. His first sculpture, which sold out pre-production is cast in bronze and now second sculpture is about to be dropped you can check out on his instagram. An artist friend of Erik’s, “Suck Lord” who creates art toys, helped him assemble the first sculpture model.

Mickey Mouse symbolizes when he tripped acid in Disney World on his 21st Birthday, ET because he Loves anything having to do with UFOs and aliens, Mario, because he is a twin and legs. One of his friends once pointed out to him that his girlfriends all have great legs, and of course, she would be holding a gun.

Erik’s First Sculpture, he calls a “Self Portrait”

His second sculpture—will be a limited edition of ten, in collaboration with “Exhibition A.” Erik told me it would be the first bronze work they have done with an artist.

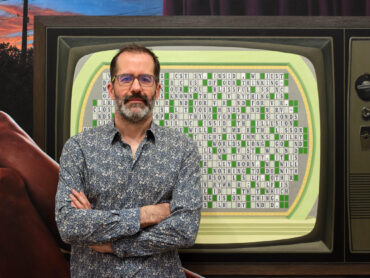

Style Anarchy

We’ve talked at length about the autonomy in his styles and mediums. He has an anarchistic viewpoint on branding himself, which doesn’t limit him, or his collectors from relishing what he creates, whatever it may be. I now own a couple of his works and can tell you as a collector, the heterogeneity of what he puts forth in his art makes it extremely fun to collect.

.

Left, “Spirit of Eden” Middle, “Laughing Gas”, Right, “Summer Camp”

We leave the studio and go for lunch with Gregory de la Haba in a small french restaurant. I had a couple of hours between meetings, and Erik offered to keep me company. He shows me his neighborhood, recounting to me how, when he first got to NYC, there was just rubble and graffiti and grime, and he loved it—pointing out older buildings that have withstood the transition over time. These are his favorite spots. We get in an uber, and he brings me to see his friend, curator and author, DB Burkeman, who recently curated a two man show in the Hamptons at N 53 Gallery that included Erik’s works. We sit with DB and we talk about music and art, some books he’s published, and one he is working on, and he shows me some of Erik’s works around the office.

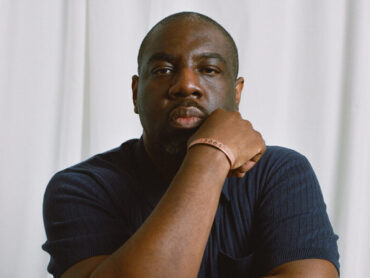

Asking DB about Erik and his work, he tells me, “Erik & I come from completely different universes, and yet we have so many things in common. Not least of all, punk rock, skateboarding culture, and our love of twisted Americana. We also dropped out of formal education too early because of learning disabilities, and both now regret that. Our personalities are very different, almost yin and yang, and yet we both intuitively feel it when someone is uncomfortable at a party. I guess we love and fight for the underdog too. I was drawn to Erik’s art before I knew him. I’ve now included something from him in all five of my books, by doing two shows at Paradigm and suggesting to friends who trust me, that they should buy his work, I feel proud that I’ve helped him become a sought after artist.”

We bid DB farewell, and Erik makes a call, asking me if I’ve ever heard of the Key Club. A few minutes later, and subsequent subway ride, we emerge in SOHO and ring a bell. Robin Winters greets us and brings us through what seemed like a labyrinth of a corridor to a large white bright room with a massively long table. People were sitting unitedly around, some working as I stare at a plant in the windowpane and think about how friendly and untroubled the vibe is in this surreal loft space above a busy city.

The scene was almost dream like, a long table. high ceilings, a cat guarding the passage to the back area and most memorably, artist Robert Hawkin standing in combat boots and suspenders, water coloring snakes, dipping his brush deftly into the water over the table, reminiscing, and making us laugh. Robin takes us past a white curtain and see some of his art, which I still think about from time to time and wonder what it looks like today. Robin makes us some tea, and we sit around the table and chat for a while before I head off. I remember taking the subway back uptown, replaying the day in my head, and felt grateful for Erik’s time and the experience and the fact I do what I love and I love it because of people like Erik.

Museums and Shows

A few months after we met, he mailed me an invite to the “American Academy of Arts and Letters” show, where he would have some of his art. I flew to NYC to see his work there and almost fell over when I saw one of the pieces he had made on the wall and immediately told him I wanted it. It was spectacular, (below left). The museum got to the work before me. Which does not surprise me at all.

Two of Erik’s works displayed at the Academy of Arts and Letters Pictured below with Donnalynn Patakos

Schooling, being schooled, learning from others and making all his dreams come true.

We discussed his education.”I rejected art school because I was a knucklehead. Now I look back, and I wish I would have gone. There were so many times I discovered the wheel, but I realized it had already been discovered. I had to learn the hardest possible way, I was so stubborn, one way or another. Owning the gallery and bar taught me so much. I wasn’t a reader. I’ve always learned things from people. I was dyslexic, and It was hard for me to read and retain that information.”

DP- How did Dyslexia affect you?

EF- “I must have been in sixth grade, and basically, I could not read, I could not tell time, I could not tie my shoes. Basic arithmetic was like Chinese to me. Mind you, my father was a mechanical engineer. They didn’t know what to do with me. I was in a school trailer where the rest of the kids had down syndrome; they gave me an IQ test to figure out what was wrong. The first test was 173. The second test was 178. The reason they did it twice was that they couldn’t believe the first one. Then the word dyslexia arrived in Pheonix. The education system had to address it. It was a new learning situation for my teacher, as well. If I was a minority and I was in the South Bronx, that would never have happened. My father had an excellent job, and I was destined to be the trust fund kid that goes to an Ivy League school, but my dad split and left my mom with nothing. We had to go to a trailer park where my grandparents lived. We went from a big four-bedroom house with a pool on the lake to a trailer park. She had to go back to work. Two women partially raised me, so I have always been more comfortable with women than men. We (he and his brother) were raised to be gentlemen.”

“When I was ten years old, my mother told me that I looked at her and told her I would be an artist, and I would live in NYC.”

Top Left- Esao Andrews, Kevin “Spanky” Long, Chad Muska, Erik Foss, Erik Ellington, Top Right- Erik and Norman Reedus, Tower Skate Park Pass, Erik and RZA from the Wutan Clan, Article in High School Yearbook, Class Picture, Chandler High School Picture, 1991, Erik and Waris Ahluwalla, Bottom Right- Ryan Gentles, Dave Grohl and Erik

So, when he was 23, he picked up his skateboard and he left Arizona for NYC, and the rest is history being made.

Today, arriving on two decades later, with an eerie similarity to NYC circa 2001, which has all but closed the nightlife industry he worked on during the last crisis. He stays put, this time making art and realizing his dream and I cannot help but admire what he has accomplished. Every once-in-a-while, I’ll receive a picture of his newest work, something he may be working on, and I smile and think that events may vex us, and situations may change, but this creatives’ life work will forever beat in the heart of NYC.