Center Stage of the Show is “Split Rock” Edition #1 , Ronan Dillion 2019

Dublin—There is a giant, flat-topped rock formation in rural Sligo County, Ireland, with an elevation of nearly two-thousand feet that the Irish call Binn Ghulbain and it juts upward and out from this coastal landscape like a magnificent, God-made inuksuk. Much like Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, Binn Ghulbain is protected and sacred, a place of lore and legend and was the spiritual home to one of the greatest literary minds of the 20th century, Ireland’s Nobel-winning poet, William Butler Yeats, who spent many of his early, formative years there and is, in fact, buried within its massive shadow. Situated on the west coast of Ireland facing the Atlantic Ocean, Sligo, or Sligeach in Irish, means “abounding in shells” and with miles of pristine coastline, Sligo’s shores roll out some amazingly good surf and one reason Ronan Dillion, the Dublin-born artist, and surfer relocated there two years ago. The other was creative experimentation and discovery in this pastoral land oft referred to as “Yeats Country”.

Split Rock, Erratic #1 by Ronan Dillion, 2019

The show’s title, Erratic, references the geological term in which a boulder, or megalith, is completely out of context from the surrounding environ and appears alien insitu. In actuality, these boulders were deposited along these parts by some glacial ablation eons ago. One boulder, aptly named Split Rock due to its large, cut-in-two incision straight down the middle and said to have been caused by a mythological warrior’s sword, is located near the artist’s favorite surf break, Easkey, and it measures 2.5 meters high by 6 meters long. Split Rock, Erratic #1, is also the largest painting in the show and its image makes up nearly half the painted surface. Portrayed in a matt, mostly monochromatic silver-gray tone, Split Rock—in all its pictorial gravitas—is more backdrop than key-player for the colorful ensemble of mark-making notations and swirls harmonically playing about and within the picture frame. The sacred natura morta becomes the stage-setting-platform for the artist to explore his particular painterly process vis-à-vis thematic ideas that have unraveled themselves to him after two productive years living in this remote territory along Ireland’s famed Wild Atlantic Way. And herein lies the modus operandi of Ronan’s poetic art.

Sligo’s “Punk Sheep”

The artist states: “Central to my practice is looking, thinking and the production of ideas. To be captivated by the magic in the every day and to share it in an accessible way.” Sligo’s magic is mystical, and humorous and can be spotted in the open fields where hundreds of thousands of sheep graze. For these are no ordinary sheep. These are punk-rocker-looking sheep with colorful wooly markings reminiscent graffiti ‘tags’ that are hand-painted by their handler-owners in bright, neon colors in order to differentiate the flocks and to distinguish which farmer owns which sheep. And just like any good street artist, these farmers have their own unique designs and signature style. Ronan has taken notes, sketches of sorts, of each farmer’s colorful identification brandings and mimics them back in his studio for his paintings. This work is often done on handmade paper crafted at Ireland’s last remaining paper mill, Griffin Mill, in Roscommon. The artist worked closely with the paper mill to combine fresh shearings from local farms with the mill’s 100% organic cotton fibers to create a paper in tune with his working environment —with his idea of making something special to place and unique in concept. The added texture more Sligo magic. The Woodville Flock Editions is the culmination of this collaboration.

‘Culleenamore, Sheep #29’Woodville Flock Edition on Paper, Ronan Dillion, 2019

Each painting is limited to a single edition, numbered and named after the precise location of each flock. ‘Culleenamore, Sheep #29’ is composed of a blue oval outline positioned off-center with spots of red, green and indigo dotting the picture. Ronan uses the same product to paint with as the farmers use to tag their sheep, ‘Agrihealth Sheep Marker’. The application, both to the sheep and to the canvas, is rudimentary and raw due to the spray can’s cap and nontoxicity which creates an “orderlessness” that the artist favors. With no super fine lines to fuss, the sheep-marker paint leaves behind a residue of speckled pigment that arbitrarily envelopes the initial and purposeful marks made by the artist, thereby allowing happenstance to conjure more magic.

Covered and tagged bales of hay in Sligo

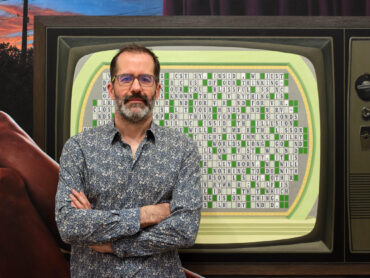

Ronan is the co-founder of me&him&you Design Studio in Dublin with clients ranging from Jameson’s to Facebook. He is a young man who clearly has a knack for making things and making things work. It’s no surprise that he sites the legendary British Graphic Designer, Alan Fletcher, who once said, “Design is not a thing you do. It’s a way of life”, as inspiration. But the design world functions on different criteria than the fine art one, the latter not needing a purpose other than to exist because it can as opposed to the former which must serve a purpose, must serve an end goal and often to a demanding client. And for the fine artist, design is more commonly referred as composition, the placement or arrangement of things, objects or people within a framework; of light and shade (chiaroscuro the Italians call it) or of abstract marks, colorful or not. In the artist’s ‘Bale Series’, Ronan brings his impeccable design sensibilities to craft dramatic and captivating imagery.

Lissadell Bale #5, by Ronan Dillion, 2019

In Lissadell, Bale #5, the artist brushes calligraphic marks using white emulsion on top of a high-gloss black surface in oil to create imagery reminiscent of Franz Kline’s black and white paintings and done so with the same strident confidence. It is important to note that in farming, bales of hay need to be wrapped tight to exclude air and moisture from getting in and most importantly to ensure a successful silage-making process. And just as the farmers tag their sheep, they’re out tagging bales upon bales of hay in the fields but this time the markings are meant to ward off black crows and to deter them from eating their crop. Ronan’s appropriation of the farmer’s bale markings and his ability to transform them into complete and unique studio work is no different than witnessing RETNA’s ability at crafting his own unique font style that came straight out of East LA’s badass Cholo Style and made legendary by the one and only godfather of said style, Chaz Bojórquez.

Ronan Dillion’s Show, “Erratic” at the Hang Tough Gallery in Dublin

The paintings in Erratic are whimsical and clever and emanate a rapid and spontaneous vigor. And Mr. Dillion suggests as much in his Artist Statement: “I’m basically taking inspiration from the farmers. In many ways, it’s the opposite of what many artists try to do, by not caring about making something aesthetically pleasing and instead of trying to make marks with speed and without care.” In his much-lauded poem, Adam’s Curse, Yeats describes the difficulty with laboring over one line to a poem and of creating something beautiful and effortless:

“We sat together at one summer’s end,

That beautiful mild woman, your close friend,

And you and I, and talked of poetry.

I said, ‘A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.”

While Adam’s Curse alludes in large measure to the book of Genesis, man’s fall and the separation of work and pleasure, it is also his plea for greater understanding for the creative process and for the people behind such process, artists. Ronan might readily admit that his paintings take no time at all. But this is where intellect, experience, and mental ardor matter as much as practice, trial and error. And to remember, too, how the artist Whistler defended his art in court when he sued the art-critic Ruskin for libel after the critic made a mockery of his simple and abstract ‘pictorial inventions’. When the judge asked Whistler how long it took to “knock off” one of his paintings, the artist replied confidently, “…a lifetime.” In a land where sheep outnumber men and waves outnumber surfers, Ronan’s two-year time away from urban madness has allotted him the necessary time away to think, and to observe, and to capture the sublime in the common, the every day, the forgotten about and he did so simply, colorfully, and effortlessly. And he recorded of his time in Sligo’s countryside a new and daring perspective of some tiny morsels of godliness, and timelessness, in the mundane and the ordinary. And we, whoever we are, are the fortunate ones. For we are left marveling and guessing, and standing still to ponder all of life’s still untapped magic and beauty our world proffers—and we must reach for it before its too late.

Gregory de la Haba