Mischa Kuball Photo by: Daniel Biskup

When Mischa Kuball published his first catalog, a slim pamphlet, in the year 1980, he had no idea that forty years later he’d be working on his 70th publication already. Books and media play a major role in his life as anyone can tell who sits down to listen to him – in his library, of course, that seemed to come to life as soon as I asked my first question about his show in an empty museum. Yep, that’s right – entirely empty!

Photo: Alexander Basile, Cologne/Germany

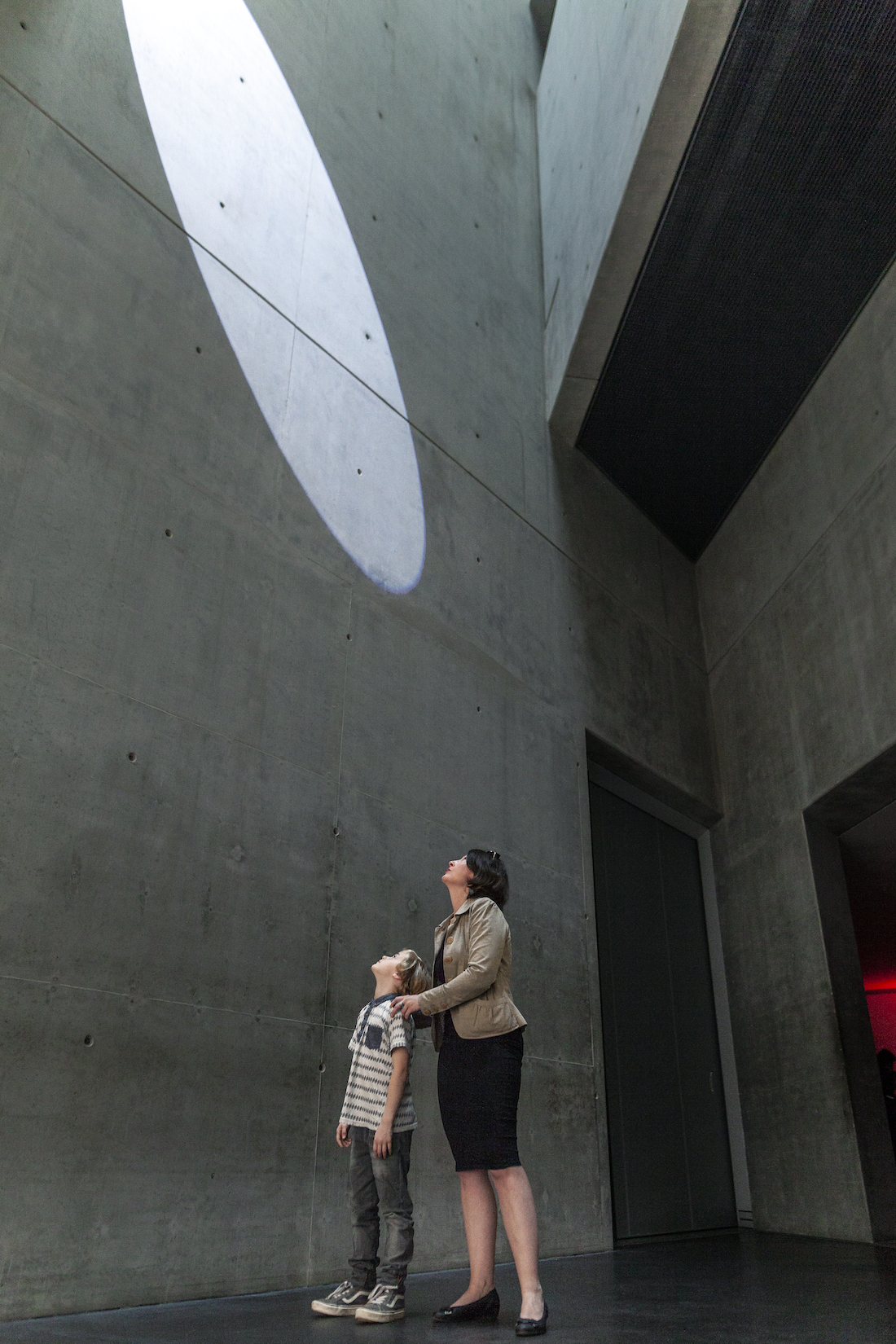

Res-o-nant is all about the lights inside Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin, Germany, and its relation to perspectives, walls, people and of course shadows. Imagine a massive building with hypnotizing inner perspectives, flights, shafts, stairs and walls like something from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

“When the building was new, half a million people came to visit the empty museum in 2001. I emptied the building again and put moving lights, mirrors and flashlights into the structure. It is all about experiencing the building anew.”

So, why the Jewish Museum of Berlin? I asked.

“Well, at first glance my show has nothing to do with Jewish culture per se because I only work in the light. We are not showing any artifacts at all. But consider this: When people congregate in a synagogue they sing, there is music! There is light, too. This is why we called the show res-o-nant. Echo! Reflection! The interaction of light and architecture is fascinating: Buildings channel light and shadows.”

Photo: Alexander Basile, Cologne/Germany

During the opening ceremony, Daniel Libeskind suggested to keep the building as it is, i.e. completely empty, and I still remember visiting the empty building eighteen years ago. It made a vivid lasting impression on me which I cannot truthfully say about a lot of exhibitions that I visited so many years ago.

“Light and concrete as materials form a rather powerful alliance and Daniel loved the idea of an empty museum filled only with light when we met in NYC before the preparations of the show even started. He was all for it, and so was his wife, Mischa laughs. “I really wanted them to be on board emotionally as well as intellectually.”

I asked Mischa about the main emotions visitors have after or during the show.

“It was interesting to see how people moved inside the empty museum”, Mischa adds with a twinkle in his eye. How so? “Well, they watched each other and emulated each other much more than in exhibitions that feature objects behind glass or in frames on the wall. As there were no objects, the visitors themselves became exhibits as it were. And they could feel it. Powerful!”

Photo: Alexander Basile, Cologne/Germany

That was an aha-moment for me as an interviewer: It never occurred to me before that the way visitors move in an exhibition could be turned into an integral part of the show itself. Now that I learned this, it seems completely obvious. This is the hallmark of a great idea!

Wasn’t it difficult to persuade the management, I asked.

“No. The museum’s director, Léontine Meijer-van Mensch gave me carte blanche. I could do whatever I wanted, no briefing, no conditions – nothing. So I emptied the entire museum first and then started thinking about the show. This is rather unusual you know? Then we asked people around the world to contribute sounds, which they did. Some 240 musicians sent us sound-files that we played unplugged. The museum just accepted it – no questions asked. They were totally open which is their creed. Very courageous curators indeed.”

Then I wanted to know more about Mischa’s relation to James Turrell, who was involved with the Jewish Museum simultaneously albeit with a separate project right outside the building. Both use light as a medium but their work has obvious differences.

“A follower of Immanuel Kant I pursue the light. My iconography is all about space and enlightenment, I don’t want to overwhelm emotionally, I want to trigger thoughts and ideas.

Another German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk once called Mischa’s work “illumination politics” in the sense that his work is focused on the individual within the constraints of society: How do we move in public spaces and how does that vision or observation affect the public spaces themselves? (If you just thought Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, you are spot on.)“Light transports messages, so I don’t want visitors to go: ‘amazing, awesome!’ I’d rather want them to think: ‘Oh, that’s interesting’, so we can have a rational conversation.By the way, Mischa successfully lobbied for James Turrell and his project in Unna, Germany, where he managed to raise a million Euro budget for one of Turrell’s works.

Patrons becoming a pat of the show Photo courtesy of Kuball by Alexander Basile

Naturally, I had to know about his next and upcoming projects, too.

“There is one about open-air sculptures by Tony Cragg in Wuppertal, Germany. They have some 30,000 visitors per year. I got invited to take part next to Henry Moore’s work and a show in Palermo, Italy. Gianluca Orlando, the city’s mayor is an iconic champion against organized crime and he invited me to do a show about Galileo Galilei and his theory about the sun:

Planets and stars are quite fascinating – not just as astronomical objects but also as political subjects.

Photo: Alexander Basile, Cologne/Germany

The way scientists talked about the stars and planets and whether people back then believed the sun revolved around the earth or the other way round really mattered at the time. It was a highly political question because it affected the way people read the bible and perceived the Vatican.”

The church didn’t exactly back Galileo’s revolutionary (get it?) insights as we all know. Mischa’s installation is about this phenomenon. “Finally, I am going on an interdisciplinary research tour of which I know nothing yet. Zero, except that it starts in Thomas Mann’s former home in Pacific Palisades, California, and is about the homeless.”

I asked Mischa how he decides whether to invest time in a project or not – having so many ideas, what is your filter?

Photo: Alexander Basile, Cologne/Germany

“This really is a problem for me,” Mischa admits, “when an issue touches me I follow that path and I always hope it won’t be too easy. Initially, I need some kind of suspicion or a hunch at least. I like to wrestle with my topics and this is what I try to tell my students, too. Become great intellectual wrestlers! Approach your subjects step by step – not everybody likes to hear this.”